|

7/22/2024 0 Comments Encourage a Sense of Wonder Me holding up a horse tail kelp found along the shore. Me holding up a horse tail kelp found along the shore. I spent a week at a cottage on the Sheepscot River, Maine, to finish the edits of my manuscript. While there, a group of children were combing the rocky shore for sea life. Their father was in the military and they had two weeks off to stay at the cottage next door before they were moving again. One of the boys, named Finn - ten years old- spent hours exploring the tidepools, finding sea urchins, baby lobster, and hermit crabs. His enthusiasm was contagious. He wore a group of necklaces that looked handmade around his neck, and bounced from one rock to another with the dexterity of a mountain goat, managing not to slip on the slick wrackweeds. Tidepools are formed during the low tide and the creatures that are left behind have adapted to living at the edge of the sea. The species that reside there are entirely different because for a period of time, twice a day, they live in suspension until the sea comes back to greet them. Their ecological niche and ability to adapt to the harsh conditions of the tides is awe-inspiring.

0 Comments

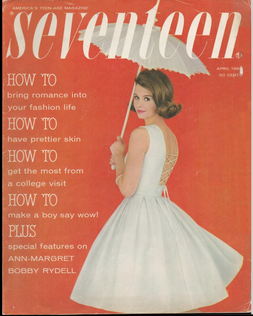

2/11/2024 0 Comments Ignore Those Who Underestimate You Around the time Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, the picture here appeared on the cover of Seventeen Magazine with the headline: How to make a boy say wow! And, at least this too: How to get the most from a college visit. The message? Go to college and find a husband. Rachel's Silent Spring unsettled a lot of scientists, specifically chemists working for the chemical industry who had everything to lose financially from her radical thesis. So they questioned it. Were we over using chemicals? Was the government not protecting its citizens? Her message rattled farmers dependent on chemicals to protect their crops from pests, and scientists who advocated DDT would eradicate pests plaguing majestic street trees like the Elm. There was also the fact that our government used DDT during World War II to protect troops stationed in Italy and the Pacific against malaria. Everything she proposed in her book went against the standards of the time. Predictably, she was ridiculed and demeaned by the press, by politicians, public figures who represented the agricultural industry, and by heads of corporations. However, she had the public in her favor. In fact, the letters to the editor of The New Yorker after Rachel's excerpts appeared in their June 1962 issue were overwhelming in her favor. Many were from state agencies of fish and wildlife that wanted copies of the magazine to distribute to politicians in their region. Luckily, an archivist saved me some time by providing a list of the handful of letters unfavorable to the article, and the majority that were favorable. So I didn't have to comb through each one. I went right to the disgruntled letters. "In any large scale pest control program in the area, we are confronted with vociferous, misinformed, ...bird-loving...citizenry that has not been convinced of the importance of agriculture..." Another wrote that her work was misleading. It produced fear and didn't educate. Another stated that her reference to the selfishness of the chemical industry is from her Communist sympathies. And we can live without birds and animals, but not business. Isn't it like a woman to be scared? There were other attacks on Rachel after Silent Spring was published in the fall of 1962. She handled it with grace. In a CBS documentary titled The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson, she didn't lose her composure as she adamantly defended her work. As a counter-point, the show also interviewed chemist Dr. Robert White Stevens who claimed if we were to follow her advice, man would return to the Dark Ages. An over-generalization if I ever heard one. In her statement before the Senate Government Operations Committee in 1963, she raised awareness that the indiscriminate application of pesticides. Their ubiquitous presence in the environment, she intimated, could be wreaking havoc on humans, and there was no effort to examine the implications at a national level. I think what she demonstrated is if you know you're right about something, people eventually come around to the same conclusion. And they come to respect you for your determination. So as long as you can hold on to your conviction, whatever that might be, without losing your dignity in the process. Source: New York Public Library The New Yorker Records. 6/27/2023 0 Comments Immerse Yourself Coralline algae, limpets, and periwinkles at the Rachel Carson Salt Pond Preserve Bristol, Maine Coralline algae, limpets, and periwinkles at the Rachel Carson Salt Pond Preserve Bristol, Maine If I was to listen to advice from Rachel Carson while writing my novel I would imagine she'd tell me to immerse myself in the places I want to write about. I've always done that, with all of my books. So no surprise I spent a week in Maine combing the same beaches she did while working on her book The Edge of the Sea (1956), and in her final years, Silent Spring (1962). I wanted to see what she saw as a fervent observer of the natural world. Rachel used the money gained from her fame as an author of the sea trilogy to buy a house on Maine's mid-coast. It was there she met and continued her special relationship with Dorothy Freeman. No wonder her cottage was a refuge, the Maine coast is picturesque and mysterious. On the day we arrived in Southport for our short mid-June vacation, a fog was creeping up the Sheepscot River into the small cove where we stayed. My husband thought it was smoke and asked "where's the fire?" That night he insisted we watch the 1980 movie The Fog to remember the creepy feeling of watching the mist roll in like a creature from another world. Perfect for a horror flick. I read somewhere the locals call it the vapors. That's making it into my novel. Then there's the tide pools. I grew up around freshwater lakes. In fact, I was eighteen when I first saw the ocean and even then my experiences have been limited to the sandy beaches of the Jersey Shore or Florida (one stint snorkeling a coral reef in Kauai). Rachel Carson was late to the ocean as well. She landed a summer scholarship to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute after college and this launched her passion to write about the sea. It's in her third book, The Edge of the Sea, she really puts her observational skills to work. Her explanation of the reproductive habits of the sea creatures is amazing, yet it's her vivid descriptions of the tidal pools, and colorful characteristics of the shifting, brimming with life ecosystems, that shine in this work. I went to the Rachel Carson Salt Pond Preserve to see what was so special about this place she called her summer home. The place where, I imagine, she allowed herself to observe, write, collect her thoughts without worldly distractions. Almost as if Lindbergh's Gift From the Sea was written about her. You have to have patience and dexterity to navigate the large boulders of the tidal pools in Maine's mid-Coast. The rocks are upended from geological faults so that they appear to have been pushed onto shore by a giant hand creating an accordion effect. The rocks glaze with crystalline striations of mica and quartz. Once I conquered the rocks, I found small pools where the ocean is trapped for a few hours while the tide is out. My view lands on a rock coated in red, submerged in a small pool of water. I identified it as coralline algae, a red algae that can secrete lime and encrust the surface of rocks. There were clumps of cladophora that resemble green mermaid hair until you pick it up and the strands feel like slime. And the rockweeds. While I was examining the tidal pools, I noticed on shore, some visitors, sitting in chairs, on the beach, on their phones. And I wondered. What is it? Why isn't this important enough? I know venturing onto treacherous rocks is not everybody's gig; I feel lucky I still can. But why not put that phone away and observe everything else? The gulls swooping in to devour whatever crabs or urchins they can discover amongst the rockweeds, the moaning of an ebbing sea, the faint clang of a line on the masthead of a sailboat moored offshore. The tidal pools in Maine made me step into a mode where I was present, not wondering what was happening later, where we'd eat dinner, just being. There's a story here that needs to be told and the only way to write it is to remember that feeling. Author note: I'll be running a workshop for Writers in the Mountains November 4th 2023 at their annual retreat on creating setting and place for your novel. 3/14/2023 0 Comments Stay Curious Rachel was first alerted to the detrimental effects of DDT while working for the government after World War II. Reports of massive fish kills at processing plants and government research facilities after widespread spraying of DDT trickled into her office at the Fish and Wildlife Service. She took note. DDT was popular with the U.S. government. It was credited for saving thousands of servicemen from getting sick while serving overseas where malaria was still a threat. After the war it was used heavily in areas to kill insects that threatened crops, forests, and urban trees. Local governments frequently blanketed whole neighborhoods with DDT to prevent Dutch Elm disease. As we know now, it didn't work. But the spraying did alarm bird enthusiasts who noticed dead robins and other songbirds blanketing the grounds after a spray. Rachel began writing about her concerns which gained the attention of people who agreed with her. They wrote her letters, letting her know about incidents in their neighborhoods. Beekeepers lost entire hives, pond owners found dead fish floating to the surface, birds collapsed at feeders, writhing in pain on the ground. She filed these anecdotes away, determined to spend more time researching the cause and effect of mass spraying of these chemicals and the consequences to wildlife, and possibly, humans. After years of collecting data from government reports, newspapers, and scientific experts, she published serialized versions of her work in The New Yorker in 1962. And all hell broke loose with the chemical industry. This was before her seminal work on the topic - Silent Spring was published. 11/28/2022 0 Comments Get Off of Social Media As famous as she was from winning the National Book Award for The Sea Around Us, Rachel was averse to public speaking and aggrandizement, much to the chagrin of her agent. When The Edge of the Sea hit the New York Times Bestseller list in the fall of 1955, she had numerous requests to speak at public events and declined most of them. She was a solid "NO" to the numerous requests from magazines to run a profile on her as well. Rachel didn't see her author life as a brand and didn't seek the attention. I'm not sure if she was afraid of the scrutiny she would receive by allowing the press into her personal life, or her natural shyness, but it doesn't mean she wasn't focused on the success of her work. Indeed, The Edge of the Sea and another book about life at the sea, albeit, a non-scientific and philosophical take, Anne Lindbergh's Gift from the Sea exchanged places on the top ten list throughout 1955-56 on various news outlets. Rachel takes note of it in letters to her friend, Dorothy. "...I truly-even now-don't expect The Edge (The Edge of the Sea) ever to reach #1 spot, but I'd be happy that it is Mrs. Lindbergh's book and not something sensational or trashy." Trashy included the book about a woman who under hypnosis discovers she'd lived another life decades earlier. After years of being at the top ten, Rachel doesn't hold back on her disdain for losing rank to Bridey Murphy (1956) which hit #1 on Chicago Tribune in 1956. "I think this silly Bridey Murphy thing is going to scoot right up and crowd Mrs. Lindbergh...The Edge by the way is No. 6- up one." And then weeks later, "That wretched Bridey Murphy thing has displaced Mrs. Lindbergh! That is really a blow. " Rachel didn't have to deal with today's social media spotlight that casts rays well beyond the reach of newspapers or magazines of her time. And she wasn't in a position to write anything with a pseudonym like Elena Ferrante, you don't get the chance to write a biography of the sea, and a scathing indictment against the chemical industry anonymously. Yet, her detachment from public scrutiny allowed her to write one of her most challenging work of all--Silent Spring (1962). And then all hell broke loose. With that in mind, I've gotten to 7k words in this novel set in Maine that has Rachel as a 'macguffin' in the story. And I'm thinking with the holidays coming, this might be time to shut down my own social media, and detach myself from that public for a few weeks so I can keep writing. Happy Holidays everyone! See you in the New Year. 11/27/2022 2 Comments Make Connections Rachel had a best friend, Dorothy. They met in Southport, Maine, where both owned a summer cottage. They wrote to each other constantly while Rachel was working on her book The Edge of the Sea (1955). In fact, Rachel dedicated the book to Dorothy and her husband Stan Freeman. Their friendship provided Rachel with stability she needed while maintaining her household (her mother passed and she had to adopt her niece's son, Roger) and adapting to her fame after winning the National Book Award for The Sea Around Us. In her letters, Rachel told Dorothy: "All I am certain of is this: that it is quite necessary for me to know that there is someone who is deeply devoted to me as a person, and who also has the capacity and understanding to share, vicariously, the sometimes crushing burden of creative effort." It may sound glamorous, but being an author means spending a boat-load of time alone. Just you and your laptop at a cafe, desk, library. Whatever. Rachel spent a lot of time writing at her home in Maryland so she could spend her summers in Maine with Dorothy. They would watch the tides, collect specimens, and listen for veeries singing in the woods. Rachel had other, less personal connections, scientists she relied on for data, editors, nature writers, and people of influence in the world of literature. Unassuming by nature, she was not shy about approaching people for assistance and guidance. That's a benefit in the world of writing. Writing, as Rachel says in another letter to Dorothy: "is hard and full of anguish and disappointments, but I also know it brings deep satisfactions and rewards that have nothing to do with best-sellerdom." Many of those satisfactions are in making connections with librarians, archivists, authors, and the many people involved in the publishing process. And let's not forget the readers. It may only take one avid fan, as Dorothy was for Rachel, motivating an author to keep going. It helps having people believe in you. Source: Always, Rachel. The Letters of Rachel Carson and Dorothy Freeman 1952-1964. Edited by Martha Freeman. 1995. 11/27/2022 0 Comments Wax Poetic In her acceptance speech for the National Book Award, Rachel Carson said this: "...no one could write truthfully about the sea and leave out the poetry." Which was why her book The Sea Around Us (1951) was so popular. Rachel had the knack for making the sea sexy. Of course, anyone who has visited the ocean is drawn to the undulating tides, but not everyone understands the machinations and the life forms dependent on them. Rachel describes it all in vivid detail. How the tides are drawn to the moon, following its waxing and waning, rising and falling with its cycles. One can visualize the neap tides, when the pull of the moon is in equilibrium with the sea and the highs and lows are not far apart. And the spring tides, twice monthly, when the moon is new or full, and the tides are at their highest. Rocks had "glistening backs...laid bare at low water." Waves are "armed with stones and fragments of rock." Her description of fog while aboard the research vessel The Albatross has an eeriness of a horror movie: "Day after day, the Albatross moved in a small circular room, whose walls were soft gray curtains and whose floor had a glassy smoothness. Sometimes a petrel fluttered across this room, entering and leaving it by passing through its walls, as if by sorcery. Evenings, the sun before it set was a pale silver disc hung in the ship's rigging, the drifting streamers of fog picking up its diffused radiance. The sense of a powerful presence felt but not seen, made manifest but never revealed, was far more dramatic than a direct encounter with the current." Her description of the grunion fish mating habits made me want to travel to California to witness it. But her words were enough to evoke the image of "shimmering" fish flinging themselves onshore on the crest of a wave. And once onshore, they lay "glittering" on the wet sand to mate. They bury their eggs before catching the next wave to return to the ocean - leaving behind their offspring. It's truly an art to distill the essence of an emotion, a place, an event in a format that is both brief and eloquent. While her musings on the sea explain the technicalities, she brings the reader to a place where even the most minute organism holds a profound secret for all. Ending her essay titled The Sea: Wind, Sun and Moon in The New Yorker, Rachel describes how the tiny worm Convoluta, no matter where placed will not forget the tidal rhythm of its being. This book was vindication for Rachel after the dismal failure of Under the Sea Wind. The New Yorker published a few chapters of The Sea Around Us pre-publication and by the time the book came out, readers were eager for more. In fact, publishing the chapters in serial format most likely propelled the book to best seller status. It stayed on the New York Times Best seller's list for 31 weeks, hitting number one. It sold over a million copies and was translated into 28 languages. I've been told once my writing allows people to feel as if they are right there in the scene. I've also had a reader ask me why my work sometimes reads commercial and other times literary. Not all readers have the patience to divert their attention from the plot to a string of words that makes them pause for a moment to savor. I'm ok with that. In fact, reading Rachel's work makes me think I may be on the right path for my next novel featuring her as one of the characters. Sources: Carson, Rachel. The Sea: Wind, Sun, and Moon. June 16, 1951. The New Yorker Carson, Rachel. The Sea Around Us. 1951. Brooks, Paul. 1989. Rachel Carson: The Writer at Work. 11/21/2022 0 Comments Accept Failure and Move One Rachel's first book, Under the Sea Wind (1941), was a flop, selling less than 2k copies. Carson chalked it up to timing - it came out on the eve of World War II - but also blamed her publisher for lack of marketing. Specifically, she was miffed that they hadn't taken her guidance on the target market - naturalists, nature lovers, sportsmen and women. Her only consolation was the rave reviews the book received from places like the New York Times, colleagues, and critics. Even so, she only netted 1k for her efforts. Rachel's need for income beyond her government salary caused her to hesitate to pay $150.00 for the rights back from Simon and Schuster for Under the Sea Wind. But when they refused to issue a reprint, she found the money. She knew she was on to something and her love of the sea and the general lack of knowledge about its secrets piqued her innate curiosity to discover more. But she was also a realist. She had mouths to feed. Her work with the Fish and Wildlife Service barely paid the bills and Rachel sought wider recognition for her talents. Bored with writing technical documents on commercial fishery production reports, she sought out stories at that might interest the general public and spin a tale she could pitch to magazines. For example, a piece on bat echolocation skills landed her a paid gig with Reader's Digest magazine. The random $150-$200 for a piece must have kept her satisfied in the creative realm but Rachel knew she was capable of more. I can relate to some of her disappointment at sales. I've spent my own money on research for the Durant Family Saga and The Truth of Who You Are. It was all worth it - staying curious is another blog post to watch for - however, as a creative you have to consider how much of your time and money to put into something and realize a pay out. In Rachel's case, she was supporting a family. Same goes for me. At times I feel as if what I'm doing may be more frivolous than art. I know I have fans that enjoy my work, but like Rachel, I've had to deal with a lot of rejection. And not much monetary compensation. I'd like to attribute Rachel's eventual success to 'grit' or stick-to-ed-ness. However, I'm inclined to think that perhaps her greatest talent (besides conveying complex scientific information in a form that is both creative and inspiring) was knowing when to move on. She kept up her oceanic research, taking notes on scientific discoveries and the latest sonar technologies. She even managed to get on a research vessel, rare for a woman in those days, observing a fish census for eight days conducted by scientists of the Fish and Wildlife Service. Feeling she had enough material to embark on a new project, she enlisted a literary agent to pitch it: The Sea Around Us - a biography of the sea that would appeal to the lay public. Oxford Press agreed to publish (1951). As was the custom in those days, she sent the first few chapters to several magazines for pre-publication and to entice an audience of potential readers. And was barraged with rejections. Readers Digest, The National Geographic, The Saturday Eventing Post - all said no. It was an editor at the New Yorker who saw the potential of her work. And things started happening for Rachel. Source: Brooks, Paul. 1989. Rachel Carson: The Writer at Work. 11/16/2022 0 Comments Stay Focused As I procrastinate on my next novel, I think back at how invested both financially and emotionally I've been to my writing life. I traveled everywhere to research the Durant Family Saga, and when I decided I wanted to turn it into a tv series, I took a course on screenwriting. I dedicated about a year to the effort, attending webinars, placing scripts in contests, paying for feedback, etc., etc. I'm pretty determined when I want to be. In fact, I've a few notebooks filled with ideas for new plots, novels, short stories and screenplays. I thrive on the creative work. But I never know what to expect from it. It's hard at times not to compare my experience with more successful authors. Rachel Carson grew up knowing the world expected something from her. In a college essay she claimed to be seeking a "fuller determination of her dreams." And she did it all without social media. She did it because she stayed focused. Although not one to pursue materialistic enterprises, her ambition did lead to financial freedom for her and her family. She grew up in Springdale, Pennsylvania in a small home with no running water or electricity. Even though the family was broke, her parents (most of all her mother) believed she had something special to contribute to the world and encouraged her to attend college. Rachel's laser sharp focus on her studies may well have been due to the fact they were always scrambling to come up with the $300 tuition to the Pennsylvania College for Women (now Chatham University), at one point selling off their dish-ware. When selling the family goods didn't prove enough, her father agreed to put up parcels of land he owned as collateral to the school. By the time Rachel graduated in 1929 she owed the college $1500.00. Her father lost his land. She went on to attend graduate school and ended up caring for her ill father, mother, and sister who was twice divorced with two daughters. They all crammed into an apartment in Baltimore where she attended Johns Hopkins University. To keep the family fed she took a job as a lab assistant in the medical school maintaining a colony of rats and fruit flies. It still wasn't enough. A friend visiting them at their cramped apartment found the family hovering over a bowl of fruit for dinner. Rachel pursued research at Woods Hole in Massachusetts where she discovered her passion for all things having to do with the Sea. She was always drawn to writing (she entered contests at an early age) and it was her ability to convey the wonders of the ocean to a lay audience that eventually propelled her to fame. But it took time. And Rachel didn't allow her family obligations to distract her from her goals. If anything, the financial turmoil she faced made her more determined than ever to make a living wage from her talents. Source: Souder, William. 2012. The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson. 11/14/2022 0 Comments Write Slow Rachel Carson Date unknown. Wikimedia/Smithsonian Collection Copyright unknown. Rachel Carson Date unknown. Wikimedia/Smithsonian Collection Copyright unknown. When people ask me what I'm working on, I tell them I'm writing a novel set on the Maine coast that centers around a young protagonist pretending to assist Rachel Carson (1907-1964) with her research in order to impress a boy. Inevitably people ask me, who is Rachel Carson? If you ever studied environmental science, as I have, you would know Rachel is famous for her non-fiction Silent Spring (1962) which upended the chemical industry, made people aware that the Bald Eagle was at risk of extinction, and is credited with STARTING the environmental movement. And I've come to learn from reading one of the many biographies about her, she was a slow writer. Yay! Something to emulate. Because the idea for writing this story has been brewing in my mind for well over three years now. I've collected all of her books, read a tome of personal letters she exchanged with her best friend Dorothy and visited the Inn along the coast of Maine where her ashes were scattered. Yet I only just started writing the novel. It's not like me to take this long. I've published five novels in the span of ten years and have three completed works, in draft form sitting on my laptop (one will never be published - it's that bad). But for some reason, I'm only at 1600 words for this novel and the motivation to write it is paralyzed by my motivation to get it just right. I'm embarking on this blog to educate and excite the reading public, to draw attention to this woman scientist, a quiet revolutionary, so I can procrastinate. Join me! And learn more about this remarkable woman and her work. Source: Souder, William. 2012. The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson. |

AuthorHi, I'm an author of contemporary and historical fiction. My next novel features a young protagonist from a lobstering family living on an island in Maine who pretends she's doing research for Rachel Carson to impress the people in her small town. Join me as I procrastinate writing the novel by blogging about Rachel. Archives

July 2024

CategoriesAll A Sense Of Wonder DDT Dorothy Freeman Environmental Movement Failure Rachel Carson Silent Spring The Edge Of The Sea The Sea Around Us Writing Writing Life |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed