Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Before it became a national park that draws more than 12 million people a year, The Smoky Mountains National Park was home to the Cherokee, and after that, settlers from Europe. They settled in the ‘coves’ or flat valley areas in the mountains which allowed them to raise crops and livestock. They had churches, schools, unique cantilevered barns, henhouses, and cabins. Thankfully, a historian had the foresight to encourage the government to preserve homesteads in the park as cultural heritage sites. And that is where the research journey for my novel, The Truth of Who You Are began. What drew me first to the region (besides the majestic mountains) were the stories of the people who once inhabited Cades Cove. The community structures are still intact, preserved by the park for visitors to witness what it may have been like growing up in the shadows of the mountains. Regional museums have books about the people who once lived in the area, how they conducted business, and lived before the government bought them out to make the national park during the Great Depression. This eleven-mile circuit holds what remains of an entire community that once lived there: homes, corn cribs, barns, smoke, and spring houses.

0 Comments

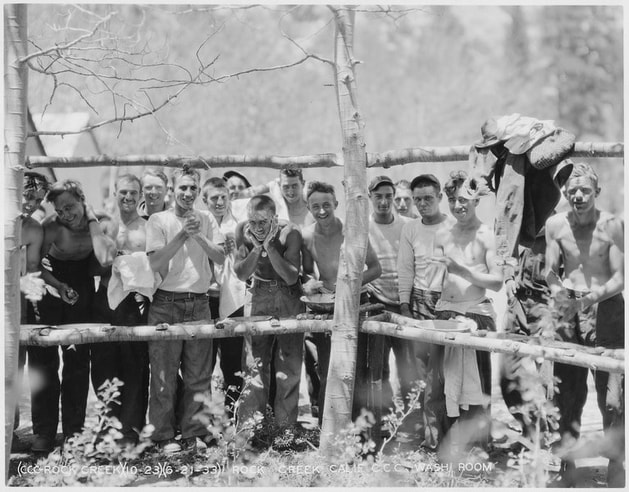

4/26/2024 Following The Past to Where It Leads MeFollow the people from the past, the places they lived, worked, politics, public sentiment, changing landscape, and a narrative emerges that's worth telling in fiction. While climbing the viewing tower on Mount Constitution in Washington State, I had the opportunity to read the testimony of the men who built it and was hooked on their story. A particular sign caught my eye. It was a certificate of appreciation to one of the men who helped build the tower in 1936, thanking him for being part of an "Army of Youth and Peace" and "Awakening the People to Conservation and Recreation." The men who built the Mt. Constitution viewing tower and much of the infrastructure at the park, served in the U.S. Tree Army, a.k.a the Civilian Conservation Corps. (CCC). They led ordinary lives during an extraordinary time in U.S. history: the Great Depression. These men, recruited from cities, rural towns and Indian Reservations from 1933-1939, served the U.S. citizenry and had an enormous impact on cultural attitudes toward conserving the natural resources, especially National and State forests. Their nickname: The Tree Army, is apt; estimates are they collectively planted over three billion trees across the country. They fought numerous forest fires ravaging lands that were cut over and neglected by private lumber companies, and they prevented the decimation of the Great Plains agricultural lands through their soil conservation works. And they were paid $30.00/month and given three meals a day to do so. The rest, $25.00, was sent home to support their families. Five dollars a month may sound like a paltry sum, but during the Depression, it was a king's salary to these men. "Five dollars a month made me rich! I never had $5.00 before in my life." They were between the ages of 17-30. Some were World War I veterans. All were on public assistance. The U.S. Surgeon General estimated that 75% of the 100,000 men they examined in one year, were malnourished, prone to disease and exhausted from stress and the search for work. As one CCC alum wrote, the men had the mark of shattered ambitions and blasted hopes written on their faces. Although the CCC was touted as a jobs recovery program, and a way to keep men, particularly immigrants from roaming city streets looking for work, President Franklin Roosevelt also had a keen interest in preserving national park land. During his administration the Federal government acquired vast amounts of land and put it in the public domain. Soon, CCC camps were popping up in rural enclaves throughout the U.S. where there were plenty of public work projects to be done. Besides planting trees these men built roads, cabins, lodges, rest areas, bridges, and scenic byways in the parks. And their presence played a big role in improving the economies of the surrounding towns. Local supplies, carpenters, and tradesmen were employed to help build and service the CCC camps and the local businesses: theaters, barbershops, food stores, all catered to them. The Tree Army had an enormous impact on the recreation and tourist industry. Back in 1930 the Great Smoky Mountains National Park had about three thousand visitors a year. By the end of that decade, and due to their work, over 130 thousand visitors came to visit. Today the park welcomes over ten million visitors/year. While reading the testimony of the men in various written accounts, one can imagine how hard it was, especially for the city dwellers, to be sent into the woods, so far from home, even if they were surrounded by awe-inspiring beauty. Most didn't have a high school education and had never traveled outside their own city neighborhoods. One man stated he and the other recruits were pensive when they landed at a Washington port to be shipped out to the San Juan Islands. They didn't believe it when they were told by their camp leader the Islands were part of the United States, instead thinking they were being deported. When Orson Welles broadcast the War of the Worlds on radio in 1938, some of the men panicked, believing their homes in the Northeast were being destroyed by an invasion of martians. As one alum recounted, the boys from the east coast cities were screamin' and hollerin' around the camp. After reading about the men in the CCC, I went looking for fictional accounts and didn't find many. That's when I decided it was time to tell their stories. In April 2022, The Truth of Who You Are was published by Black Rose Writing. A coming of age story about hope and resilience and set at one of the CCC camps in the Smoky Mountains NP. Sources:

Olympic Mountain Range from Mt. Constitution, Moran State Park, Orcas Island. Photo credit Wikimedia: Lee317 Brinkley, Douglas. Rightful Heritage. HarperCollins 2016. Hill, Edwin. In The Shadow of the Mountain. Washington State University Press 1990. Jolley, Dr. Harley. The Maginficent Army of Youth and Peace. UNC Press. 2007. Maher, Neil. Nature's New Deal. Oxford University Press 2009.  Apple Trees by Levi Wells Prentice circa 1890 Source: Wikimedia Apple Trees by Levi Wells Prentice circa 1890 Source: Wikimedia Drive through any rural area of the U.S. and you will inevitably find apple orchards; some may be new, others may be reminders of a family homestead long abandoned. But the trees remain. It's believed that the Pilgrims brought apple seeds with them to the American colonies when they arrived in the early 1600s and grafted the European variety with the native American species of crab apple. Over the years farmers created many new varieties of apples. But not for eating. Apple trees and orchards had other economic uses. One of the first things a settler would do is plant an apple orchard as a way to stake claim to a parcel of land. When investors formed the Ohio Company to lure colonists from the eastern states further West, they insisted the settlers plant at least fifty apple trees to establish their claim. Apples provided an important part of the American diet: cider. Most colonists used their apples to make cider, which was safer to drink than water. Indeed, one of out of every ten farms in New England operated a cider mill. Estimates are that an average New England family consumed about 35 gallons per person per year. (The author, Tracy Chevalier, wrote a historical novel centered around a family in Ohio that grows cider apples titled At the Edge of the Orchard. Although dark, it includes a fascinating botanical history.) By the mid 1700s, orchards were an integral part of the American landscape. And although it may be assumed that the European settlers were the only ones to plant orchards, there was ample evidence that Native Americans also incorporated orchards into their lifestyle. In 1779, a scout for the Revolutionary Army drew a map of the Cayuga and Seneca native American settlements in the Finger Lakes region of New York. As the map shows, there were numerous orchards dotting the landscape. General Sullivan, ordered his soldiers to go into the villages and wipe out the crops in retribution for an Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) incursion against the army. One soldier wrote in his diary about an attack on a village in what is now Geneva NY: we found about 80 houses something large some of them built with hew and timber and part with round timber and part with bark. Large quantities of corn and beans with all sorts of sauce, at this place a fine Young Orchard, which was soon all girdled. 1/25/2022 1 Comment The Book That Won't Quit Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash About five years ago I was on a trip in the Orcas Islands when I learned about the men in the Civilian Conservation Corps who worked for a measly $5.00/week during the Great Depression, building infrastructure and planting over 1 billion trees in our nation's parks. Of course I'd heard of these men but never knew much about their work or their history. But after reading about the Corps, the multitude of men who hearkened from diverse geographic backgrounds, many of them first and second generation immigrants, I felt compelled to tell their story. I hadn't realized it at the time, but this book project titled The Truth of Who You Are, would become an emotional journey for me that had me doubting myself time and time again. Was it worth it? I kept asking. Let me list the tribulations to see this novel through to a publishing deal. 1) Research - since the novel is historical, I had to do research, which meant traveling to some of the sites where these men worked. Being self-funded, I launched an online crowdfunding campaign. I made a video, which took hours, and I almost made my goals. But the campaign failed and I wrote about it here. So I scaled back my travel plans to something doable - research in the Smoky Mountains, near where my parents lived in South Carolina. There was a lot of history to work with and hey, it's a tax write off, right? 2) Contests - I am a sucker for them. After winning one literary contest in 2017 for my novel The Night is Done, I figured I might be in a roll, so why not enter my work in progress to some contests , see how it goes? I entered The Truth of Who You Are in five writing contests. It gained semi-finalist status in one, and lost in two others. One is still pending. But the most heartbreaking loss was a national, prestigious contest that required I not pitch the book to anyone, no agents or publishers, until they told me it was out of the running. Five months later and two weeks before they were going to announce the winner, I still hadn't heard anything. My novel was still in the running. I couldn't believe it. The prize was $25,000 and a publishing contract. Could it be that The Truth of Who You Are had won? Everyday that I opened my email and there was no rejection I got my hopes up. My anxiety level was through the roof. I told only a few select friends and family about my anticipation. And then....rejection. 3) Publishers and Agents- I've attended numerous conferences over the past few years, pitching this novel to agents and editors at publishing houses. One editor wrote back to me with constructive feedback as well as encouraging words. "The Conservation Corps sections are terrific, I think. They really conjure time and place and show the impact of the programs on the people who participated in them and on the communities they served. And the burgeoning romance is nicely done as well." Yay! I revised and resubmitted. It was rejected. That was one of many to come from other agents and publishers, after they requested to read the whole manuscript. 4) Revise, revise, revise - the next step in the process is always to self-reflect, reexamine the manuscript and revise. At some point though one has to decide. What is the issue here? Is this novel not marketable? What do people want? Many revisions later, I adjusted the concept, and started all over again with the pitching. 5) Publishing Contract - I sent the novel to a small publisher who offed me a contract. Yay! Then I read the contract. That and a few other things led me to believe I'd be no better off than if I published it myself, so I declined. I can't even begin to tell you what a gut wrenching decision that was. 6) Giving up - I firmly believe in this novel. I know what it feels like to not believe something is worth pursuing. I have a novel I wrote about smuggling along the US/Canadian border sitting on my laptop which will never see print. But this novel, The Truth of Who You Are, is different. I've had positive feedback from several readers, people who I've only met in online writing circles. And my critique partner, who is brutally honest, told me it is my best writing so far. Recently a publisher asked me for the full manuscript and I’m waiting for their response. Their contract is posted on their website and seems more favorable. So we'll see. Like I said, this book won't quit. But I imagine, neither did these guys from the Conservation Corps. Post script: I wrote this blog in November 2019 and have since signed a contract with Black Rose Writing to publish. The novel launches April 28, 2022. You can pre-order (discounted) ebooks at the following links. 4/8/2020 Enough Already! Main entrance NY Public Library. Main entrance NY Public Library. In a interview on the History Author Show podcast about the Durant Family Saga, the interviewer asked me a question that had me stumped: If you could fill any gap about this fascinating family after three novels, what would you choose? Of course, there’s more I could have uncovered about the Durants to turn my trilogy into a series. I've received emails from people who were reading my books and my research journey blog. They offered me tidbits of information, leads to follow, contact information of descendants with interesting histories of their own. But for me, enough was enough. I’d spent five years of my life researching this Gilded Age family. I had traveled to several libraries and museums on the east coast of the U.S., and visited the Isle of Wight in England. At some point authors of historical fiction rely on conjecture. It is the lens we use to offer our interpretation of events given the information we have on hand. Indeed, at the end of the trilogy, in the novel, The Night is Done, the narrator, a historian, remarks: I’m sure that in the future, someone will come along and find gaps in my research. It’s the historian’s curse. Our job is to sift through the tall tales and determine what’s worth including and what’s best left as fodder for others to chew on. The truth is found in the abyss of the unknown. If my readers believe it’s me, the author saying these words, they aren’t far off. I put myself in the head of the narrator, a historian, tracking down and interviewing an elderly member of the Durant family, and by the time I was done writing the last book in the trilogy, it was how I felt. We read historical fiction to discover history in an interesting and entertaining fashion. Authors of this genre are all too aware that some research could take up a lifetime and if we wait for all the facts to be known, the stories would never get written. This is especially true as libraries, newspapers and museums digitize their collections making them more accessible to the public, uncovering new details and facts about historical events along the way. There are always new stories to tell, and I have moved on to tell them. My latest work in progress is about the men of the US Civilian Conservation Corps, who planted over a billion tree seedlings in the US during the Great Depression. The story revolves around the families who once lived in Cades Cove, a cultural heritage site at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. After doing research about these families, I felt compelled to tell their stories. And I hope to have this novel published soon.You can read the first couple of chapters here.  The sound of a stream plunging over a precipice is one sign of spring and on my recent visit to the Smoky Mountains National Park there were plenty of gushing waterfalls; I hiked up to Spruce Flats to get this view.  I went to the Smoky Mountains National Park to conduct research for a novel and to write about place, exploring the mountains in spring. I was especially interested in the area around the Tremont Institute in the park. It was once a thriving lumber community and one of the more famous inhabitants was William Walker. He owned most of Walker Valley before the Smoky Mountains National Park was formed, and this is where my fictional family lives. What drew me to their story is the old growth, or what is left of it at the Tremont Institute in the park. William Walker settled here in the 1850s and as lumber operations closed in on his valley, he tried to keep his old growth woods from the clutches of the Little River Lumber Company. William lived a colorful life. According to his descendants, he had three wives and some estimate he sired over 20 children. He hung on to his land until 1918, selling it off to the owner of the Little River Co. on his death bed with the understanding that the old trees would be spared. What he never knew was that eventually his trees were cut, post-mortem, by the company and that he was under paid for the land. A few miles down the road from Tremont and Walker Valley is the only cultural heritage site in the park - Cades Cove. This eleven mile circuit holds what remains of an entire community that once lived there: homes, corn cribs, barns, smoke and spring houses. The people that lived in Cades Cove had full, industrious lives.  A cove is another name for valley. Large area of flat land between mountains. A cove is another name for valley. Large area of flat land between mountains. Their economy was based on a bartering system with the nearby cities and towns. And they had plenty to barter before the woods were ravaged by blight, forest fire, and habitat destruction. Ginseng, chestnuts, corn, and cattle were just some of the products the people of Cades Cove bartered and sold at markets in Maryville and Knoxville, TN. Luckily local residents (many descendants) from nearby Townsend, Tennessee advocated for preserving the architecture of Cades Cove. It is the only area in the park where you can find everything intact. Which was fortunate because when the government started acquiring land for the park in the mid-1920s they tore down or let buildings rot after their occupants moved out. Just like the natural areas in the park, Cades Cove is a great place to rocket the imagination. I also found a plethora of reading material at the Smoky Mountains Heritage Museum in Townsend, first hand accounts from people who grew up in the region before their families were forced to move because of the National Park in the mid 1930s. These books are gold mines of information, tall tales, and stories about the families who lived there, their hardships, feuds, and industry. Before a fungus blighted the Chestnut trees, children would go deep into the woods to collect the nuts and sell them at the local stores. They had a miller who came in from the fields at the sound of a bell to mill corn for customers who stopped in with a sack of kernels. His was an important job as corn was a family staple and wheat was hard to grow so flour was usually shipped in and store bought. The families raised pigs, notched their ears to identify them and let them roam the hills. At harvest time they were lured in with salt and nuts. The meat was kept in a smokehouse and slabs taken off throughout the winter. Game was scarce by the early 20th century due to over hunting. Hunters were lucky to get a 'Gobbler' roosting in a tree, or squirrel meat. I found no references for deer hunting but Elk now pasture in the coves and there are signs everywhere to be aware of them while driving. I've visited the park twice and have yet to see one. But I'll be back for the next season: summer and maybe I'll get lucky. Connect here for my next post on the history of lumber industry in the Smoky Mountain region.

1/30/2020 The Anatomy of a Historical Novel Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn NY Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn NY Often, when I'm giving a talk about my novels I'm asked, where did you come up with the idea to write the story? I get my inspiration from past. I started to research the Durant family saga - after staying in a cabin hidden in the wilderness that was supposedly built by William West Durant for trysts with his mistress. What I thought would be a one book love story/romance, turned into a four year research journey. This folklore about William and his mistress started me down a path of clues that shed light on the lives of the Durant family and had me visiting the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, Winterthur Museum, the Adirondack Museum, and England. My one book idea turned into a trilogy. Soon after I was finished with my draft of novel three in the trilogy, I was visiting my family in South Carolina and ended up hiking in the Great Smoky Mountains, one the US most popular National Park. I was intrigued with the history of the people who once lived in the park and were eventually forced out--like the residents of Cades Cove--now a Cultural Heritage site in the park. And then there is the story of the Walker Sisters, who, due to their age, were allowed to stay in their cabins until they died. I found fascinating oral histories about the former residents in the bookstore of the Smoky Mountains Cultural Heritage Museum in Townsend, TN. While the research is a slow and steady task, never really ending, a lot of it can be done via use of digital archival material. However, the writing takes dedication. I'm lucky enough to be in an academic profession that allows me chunks of time to write. In the summer months I spend the mornings in a library or coffee house writing until I reach 3k words (usually about two-three hours). I do this until I have a rough draft of a novel - about 80k words. Editing takes another year if not more. Indeed, I am still editing the novel I wrote set in the Great Smoky Mountains, The Truth of Who You Are, as it is now out on submission with publishers. Once in a while I panic, thinking, will I ever run out of ideas on what to write about? What if this novel is my last? Can I keep up with the research and the creative process involved in putting out a novel set in the past about real people and events? Recently, while walking in the famous Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn, NY where Harriet Tubman, and William Seward are buried, I thought about how many stories there are to tell and thought, "I'll ever run out of material." 12/6/2018 Writing Alone In the Wilderness It sounded like a good idea at the time: a week at a cabin built in 1890 on Raquette Lake, NY. The perimeter of the lake is 95% public land, part of the Adirondack Park wilderness and the cabin is part of a compound owned by a state college. It has no electricity, no wi-fi, no cell phone coverage, and is only accessible by foot or boat. It would be idyllic, a haven of peace away from the tumultuous clamor of modern life. A place to write my novel.  Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash Photo by John Schnobrich on Unsplash Writing historical fiction, I have come to learn, is like navigating a slippery slope along a precarious cliff. God forbid you get a fact wrong. Anyone who knows anything about the time period you are writing about will let you know that you did: in the reviews, on the internet, for all to see. Let’s face it. Getting the clothing down, the setting, the politics and social graces of the times is the easy part. Keeping people entertained in another time period is what makes the story a story. So I have had to take liberties as well in my saga about the Dr. Thomas C. Durant family and their quest to open up the Adirondack wilderness to the New York City elite. Here are my list of reasons why a writer may look beyond known facts to add more drama to a story as a way to lure in the reader/viewer. 1. When your main aim is to entertain the readers more than educate them. This is a fine line. Many readers of historical fiction, and tv audiences want to see the characters in the appropriate dress, eating customary food, and displaying the correct mannerisms of the time period. Indeed, I read a review of the Downton Abbey fox hunting episode and equestrians from all over the world had written in complaining that one of the female characters was not holding her riding crop correctly. Jeesh. Were people really paying attention to that? I guess so. That kind of scrutiny puts a lot of pressure on the writers of these scenes. I am convinced however that what really keeps the majority of the tv audience watching Downton Abbey is the soap opera happening upstairs in the dining hall, and down stairs in the scullery. 2. When the known facts don’t explain WHY something happened, or to clarify the characters and motives of the protagonists, even if you have to invent them. I am dealing with this one. One of my main characters: William West Durant, spent a huge portion of the family fortune building Great Camps in the Adirondack wilderness that never turned a profit. Indeed, when he sold these camps off to the Vanderbilts and Morgans, he LOST money. As he was bleeding out the family fortune with these artistic ventures, he also had the audacity to commission a $200,000 yacht (that’s close to $4 mil. in today’s US dollars) and used it to sail to Cowes and hang out with his old aristo buds at the annual royal yachting events. In the meantime, his sister was suing him for her share of the inheritance. Why then, did he flaunt his obvious wealth to all of their family friends while she was on an allowance of $200/month in London? Did he think she wouldn’t notice? Because William W. Durant didn’t keep a diary explaining all of his motives, he only admitted years later to his oral biographer that as a youth he had never learned how to make money, just how to spend it. But is that an excuse for his scandalous behavior toward his sister? I have to get into William’s head somehow, and use fiction to help the reader believe his motives as I predict them. 3/14/2018 Why I Wrote a Trilogy I stumbled upon a review of my first novel in the Durant Family Saga: Imaginary Brightness. It was not entirely unflattering, not glowing either, but I appreciate anyone taking the time to post on social media their opinion of my chronicle of the family of the famous robber baron Dr. Thomas C. Durant. However, I realized while reading it, the reviewers were dismayed I ended the story abruptly because they wanted to know more about what happened to Durant family siblings. So to be clear, readers, understand this: I wrote a trilogy. I had to. I don't like reading long books. Maybe that's why, in a recent visit to the library, I picked up The Gilded Hour, Sara Donati's 737 page fictional tome about two spinsters, both medical doctors working in New York City in 1883. I started reading it against my good judgement and have not been able to put it down since. This does not bode well for me, as I have to finish other books for work, and for my monthly book club meeting. In all fairness, I can't behoove any author who chooses to write these long works of fiction. If one has the time and inclination, one can get caught up in a time and place for hours, days, and at the rate I read, weeks. But when I had to decide what to do with all of my research, I decided early on to write a trilogy. I had too much material to cram into one book, or so I thought, knowing I favor books that are 300 pages in length. And there has been an advantage to me to do so. Firstly, I kept discovering new material. Old newspaper articles that I may have missed before would pop up in my research to reveal that one of my characters spent time training to be a nurse in England. An archivist for New York City court emails me he found a long lost divorce case file, now if I could just get my hands on it. I had time. It would all come out in book three after all. Secondly, the brief interlude between books allowed me the luxury to mull over my characters and their motivations. A recent breakfast meeting with one of my beta readers changed my whole perspective on how I was planning to write the narrative of the downfall of one of my main characters in book three. We contemplated: was he an egotistical maniac or a true artist at heart? These types of meandering thoughts come at a snail's pace. They don't just pop up in my head without a lot of debate and thought. I like the process of peeling away at the characters in my story, one book at a time. And I like the idea that my novels are readable in one month for those people, like me, who live busy lives. I'd hate to think people might be racing through my descriptive narrative to get to the end of the story, which is what I sometimes find myself doing when I become impatient with a story. Or maybe I'm just spoiled, like so many people these days, expecting instant answers to my question: what will happen next? To be honest, I'd have to admit that at least the author of The Gilded Hour provided me closure in one reading. My poor readers had to wait until I figure out how to write the last book in the trilogy. Lucky for them, the third book, The Night is Done, is now available. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed