Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Before it became a national park that draws more than 12 million people a year, The Smoky Mountains National Park was home to the Cherokee, and after that, settlers from Europe. They settled in the ‘coves’ or flat valley areas in the mountains which allowed them to raise crops and livestock. They had churches, schools, unique cantilevered barns, henhouses, and cabins. Thankfully, a historian had the foresight to encourage the government to preserve homesteads in the park as cultural heritage sites. And that is where the research journey for my novel, The Truth of Who You Are began. What drew me first to the region (besides the majestic mountains) were the stories of the people who once inhabited Cades Cove. The community structures are still intact, preserved by the park for visitors to witness what it may have been like growing up in the shadows of the mountains. Regional museums have books about the people who once lived in the area, how they conducted business, and lived before the government bought them out to make the national park during the Great Depression. This eleven-mile circuit holds what remains of an entire community that once lived there: homes, corn cribs, barns, smoke, and spring houses.

0 Comments

12/1/2022 2 Comments Gendered Ethnographies Anyone researching the Appalachian culture at the turn of the 20th century is likely to find the ethnographies of Emma Bell Miles and Horace Kephart. Miles’ The Spirit of the Mountains (1905) and Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders (1913 and 1922) document the daily lives of the people living in the mountains of the southeast United States in the early 1900s. Their lyrical prose on the familial culture, unique dialect, art and music—influenced by isolation—are entertaining and insightful reads. Emma was the inspiration for Ben Taylor's mother, in my novel The Truth of Who You Are, set in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. I found her personal story both tragic and inspiring. And the contrast of Emma Bell Miles' fate compared to Horace Kephart, (considered legendary in the region for advancing the National Park) smacks of irony. So I delved into to their personal lives further. And this is what I found. An examination of these two authors reveals parallels in their writing style and the influence their education had on their perception of the culture. Emma went to college for two years at the St. Louis School of Art. Horace attended college in the mid-west and then went on to graduate school at Cornell University in 1881 to study history and political science. Both authors had educations that were for the most part beyond that of the people they were studying. Rather than condescending, the authors had a penchant for describing their neighbors with grudging respect and awe for their resiliency. Moreover, both authors were amateur naturalists. Kephart wrote numerous articles for magazines such as Field and Stream on camping and the flora and fauna of the region, while Miles wrote and illustrated a book titled Our Southern Birds, in 1919. Both weave vivid narratives of the natural beauty of the region throughout the Spirit of the Mountains and Our Southern Highlanders.  The sound of a stream plunging over a precipice is one sign of spring and on my recent visit to the Smoky Mountains National Park there were plenty of gushing waterfalls; I hiked up to Spruce Flats to get this view.  I went to the Smoky Mountains National Park to conduct research for a novel and to write about place, exploring the mountains in spring. I was especially interested in the area around the Tremont Institute in the park. It was once a thriving lumber community and one of the more famous inhabitants was William Walker. He owned most of Walker Valley before the Smoky Mountains National Park was formed, and this is where my fictional family lives. What drew me to their story is the old growth, or what is left of it at the Tremont Institute in the park. William Walker settled here in the 1850s and as lumber operations closed in on his valley, he tried to keep his old growth woods from the clutches of the Little River Lumber Company. William lived a colorful life. According to his descendants, he had three wives and some estimate he sired over 20 children. He hung on to his land until 1918, selling it off to the owner of the Little River Co. on his death bed with the understanding that the old trees would be spared. What he never knew was that eventually his trees were cut, post-mortem, by the company and that he was under paid for the land. A few miles down the road from Tremont and Walker Valley is the only cultural heritage site in the park - Cades Cove. This eleven mile circuit holds what remains of an entire community that once lived there: homes, corn cribs, barns, smoke and spring houses. The people that lived in Cades Cove had full, industrious lives.  A cove is another name for valley. Large area of flat land between mountains. A cove is another name for valley. Large area of flat land between mountains. Their economy was based on a bartering system with the nearby cities and towns. And they had plenty to barter before the woods were ravaged by blight, forest fire, and habitat destruction. Ginseng, chestnuts, corn, and cattle were just some of the products the people of Cades Cove bartered and sold at markets in Maryville and Knoxville, TN. Luckily local residents (many descendants) from nearby Townsend, Tennessee advocated for preserving the architecture of Cades Cove. It is the only area in the park where you can find everything intact. Which was fortunate because when the government started acquiring land for the park in the mid-1920s they tore down or let buildings rot after their occupants moved out. Just like the natural areas in the park, Cades Cove is a great place to rocket the imagination. I also found a plethora of reading material at the Smoky Mountains Heritage Museum in Townsend, first hand accounts from people who grew up in the region before their families were forced to move because of the National Park in the mid 1930s. These books are gold mines of information, tall tales, and stories about the families who lived there, their hardships, feuds, and industry. Before a fungus blighted the Chestnut trees, children would go deep into the woods to collect the nuts and sell them at the local stores. They had a miller who came in from the fields at the sound of a bell to mill corn for customers who stopped in with a sack of kernels. His was an important job as corn was a family staple and wheat was hard to grow so flour was usually shipped in and store bought. The families raised pigs, notched their ears to identify them and let them roam the hills. At harvest time they were lured in with salt and nuts. The meat was kept in a smokehouse and slabs taken off throughout the winter. Game was scarce by the early 20th century due to over hunting. Hunters were lucky to get a 'Gobbler' roosting in a tree, or squirrel meat. I found no references for deer hunting but Elk now pasture in the coves and there are signs everywhere to be aware of them while driving. I've visited the park twice and have yet to see one. But I'll be back for the next season: summer and maybe I'll get lucky. Connect here for my next post on the history of lumber industry in the Smoky Mountain region.

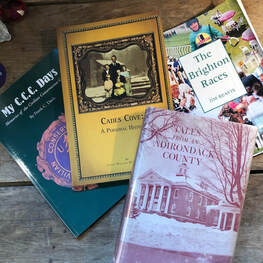

1/8/2019 Preserving Public History This is an ode to those public historians who went out of their way to write and publish local history that would otherwise have been forgotten. Whether it was about their own past experience, or the history of a place, these books are gems for those of us writing historical fiction. They are accounts of the ordinary people, ones who may not have been famous, but whose lives are the fabric of the past. I've found my share of these treasures while researching my novels. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed