Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Before it became a national park that draws more than 12 million people a year, The Smoky Mountains National Park was home to the Cherokee, and after that, settlers from Europe. They settled in the ‘coves’ or flat valley areas in the mountains which allowed them to raise crops and livestock. They had churches, schools, unique cantilevered barns, henhouses, and cabins. Thankfully, a historian had the foresight to encourage the government to preserve homesteads in the park as cultural heritage sites. And that is where the research journey for my novel, The Truth of Who You Are began. What drew me first to the region (besides the majestic mountains) were the stories of the people who once inhabited Cades Cove. The community structures are still intact, preserved by the park for visitors to witness what it may have been like growing up in the shadows of the mountains. Regional museums have books about the people who once lived in the area, how they conducted business, and lived before the government bought them out to make the national park during the Great Depression. This eleven-mile circuit holds what remains of an entire community that once lived there: homes, corn cribs, barns, smoke, and spring houses.

0 Comments

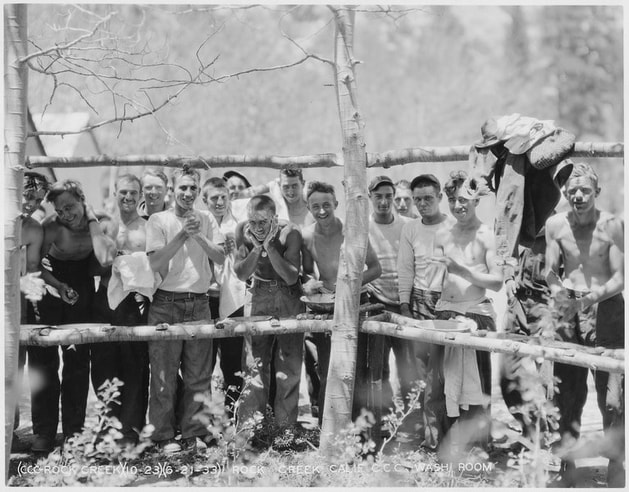

4/26/2024 Following The Past to Where It Leads MeFollow the people from the past, the places they lived, worked, politics, public sentiment, changing landscape, and a narrative emerges that's worth telling in fiction. While climbing the viewing tower on Mount Constitution in Washington State, I had the opportunity to read the testimony of the men who built it and was hooked on their story. A particular sign caught my eye. It was a certificate of appreciation to one of the men who helped build the tower in 1936, thanking him for being part of an "Army of Youth and Peace" and "Awakening the People to Conservation and Recreation." The men who built the Mt. Constitution viewing tower and much of the infrastructure at the park, served in the U.S. Tree Army, a.k.a the Civilian Conservation Corps. (CCC). They led ordinary lives during an extraordinary time in U.S. history: the Great Depression. These men, recruited from cities, rural towns and Indian Reservations from 1933-1939, served the U.S. citizenry and had an enormous impact on cultural attitudes toward conserving the natural resources, especially National and State forests. Their nickname: The Tree Army, is apt; estimates are they collectively planted over three billion trees across the country. They fought numerous forest fires ravaging lands that were cut over and neglected by private lumber companies, and they prevented the decimation of the Great Plains agricultural lands through their soil conservation works. And they were paid $30.00/month and given three meals a day to do so. The rest, $25.00, was sent home to support their families. Five dollars a month may sound like a paltry sum, but during the Depression, it was a king's salary to these men. "Five dollars a month made me rich! I never had $5.00 before in my life." They were between the ages of 17-30. Some were World War I veterans. All were on public assistance. The U.S. Surgeon General estimated that 75% of the 100,000 men they examined in one year, were malnourished, prone to disease and exhausted from stress and the search for work. As one CCC alum wrote, the men had the mark of shattered ambitions and blasted hopes written on their faces. Although the CCC was touted as a jobs recovery program, and a way to keep men, particularly immigrants from roaming city streets looking for work, President Franklin Roosevelt also had a keen interest in preserving national park land. During his administration the Federal government acquired vast amounts of land and put it in the public domain. Soon, CCC camps were popping up in rural enclaves throughout the U.S. where there were plenty of public work projects to be done. Besides planting trees these men built roads, cabins, lodges, rest areas, bridges, and scenic byways in the parks. And their presence played a big role in improving the economies of the surrounding towns. Local supplies, carpenters, and tradesmen were employed to help build and service the CCC camps and the local businesses: theaters, barbershops, food stores, all catered to them. The Tree Army had an enormous impact on the recreation and tourist industry. Back in 1930 the Great Smoky Mountains National Park had about three thousand visitors a year. By the end of that decade, and due to their work, over 130 thousand visitors came to visit. Today the park welcomes over ten million visitors/year. While reading the testimony of the men in various written accounts, one can imagine how hard it was, especially for the city dwellers, to be sent into the woods, so far from home, even if they were surrounded by awe-inspiring beauty. Most didn't have a high school education and had never traveled outside their own city neighborhoods. One man stated he and the other recruits were pensive when they landed at a Washington port to be shipped out to the San Juan Islands. They didn't believe it when they were told by their camp leader the Islands were part of the United States, instead thinking they were being deported. When Orson Welles broadcast the War of the Worlds on radio in 1938, some of the men panicked, believing their homes in the Northeast were being destroyed by an invasion of martians. As one alum recounted, the boys from the east coast cities were screamin' and hollerin' around the camp. After reading about the men in the CCC, I went looking for fictional accounts and didn't find many. That's when I decided it was time to tell their stories. In April 2022, The Truth of Who You Are was published by Black Rose Writing. A coming of age story about hope and resilience and set at one of the CCC camps in the Smoky Mountains NP. Sources:

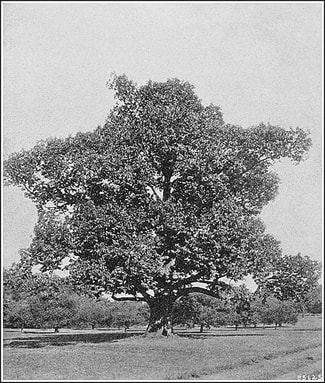

Olympic Mountain Range from Mt. Constitution, Moran State Park, Orcas Island. Photo credit Wikimedia: Lee317 Brinkley, Douglas. Rightful Heritage. HarperCollins 2016. Hill, Edwin. In The Shadow of the Mountain. Washington State University Press 1990. Jolley, Dr. Harley. The Maginficent Army of Youth and Peace. UNC Press. 2007. Maher, Neil. Nature's New Deal. Oxford University Press 2009.  A red maple planted with students. A red maple planted with students. I've used this tag line in my biographies several times and although it's metaphorical, it's also true. In my professional capacity over the years as an outdoor educator and professor teaching ecology and environmental science, I've worked alongside volunteers and students planting trees. Together we've planted hundreds of seedlings and bare root mature trees in places such as the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, the City of Syracuse parks, and the nature trail behind the college campus where I teach. So you can imagine my chagrin when we were approached by the utility company with a request to take down the ash trees that line the front of our house. The Emerald Ash borer is wreaking havoc on ash trees in the Northeastern U.S. and our ash trees are directly under the utility wires. The emerald ash borer beetle lays eggs in the tree's bark and the larvae eat away at the phloem, the inner part of the bark that transports water and nutrients, eventually killing the tree. The borer is not native to the United States and was brought to the states accidentally in 2002 from Asia. Within the decade our trees would be dead so we agreed to let the utility take them down. We then had to decide whether to take down the magnificent ash tree in our side yard.  This tree was planted long before we arrived, I'm guessing its age at fifty plus years. Its largess allowed it to throw shade on the back deck. Great! Except when you live in Upstate, NY and summers are so short. Half the tree hung over the driveway and in the fall it shed dead limbs and leaves like crazy. We spent hours cleaning up the mess it left on the pavement after a wind storm. So although I loved the tree we decided to take that one down as well. As upsetting as it was to see the hole in the sky when the tree was felled, this summer we've witnessed spectacular sherbet colored sunsets now that the limbs aren't obstructing the view.  It wasn't long however before the gaping hole in the landscape gnawed at me and we went in search of a new tree. I chose a redbud because I love the way their lavender flowers bloom so delicately in the spring. And they don't get that big - maybe twenty-five feet in height. Even as we were debating whether to take the ash tree down I knew I'd end up planting another in its place; I've spent the past few decades educating and advocating for the natural world. And I'm always rewarded by the look of wonder and accomplishment that passes over people's faces after grubbing around in the dirt, digging holes, putting in a tree, heeling the rich earth back into place. I remember one day in particular while planting thirty trees with my students in the nature trail behind campus. I was crouched over a dug-out hole, wide enough to handle the bare roots of a red maple. I was working with a student, using a shovel to back-fill the hole with dirt, when the student told me, "I've never planted a tree." He sat back on his haunches sweating and wiping at his brow with the back of his hand. "Well," I told him, "this is something you won't forget." I eyeballed the sky. "And if you do, come back one day to see how much it has grown."  American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia The story of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) is tragic but hopeful. At one time the Chestnut tree was prolific in the northeastern US. At the turn of the 19th century, the Chestnut covered over twenty-five percent of the Appalachian mountain range which runs from Maine to Georgia. However, an imported fungus first discovered in 1904 destroyed much of the Chestnut forests. The Chestnut tree was an integral part of the landscape and had many uses. Indigenous people had multiple names for the tree's nuts, which they ground them down for flour. Families that moved into the Appalachian region foraged the nuts to eat and sell. But people weren't the only consumers of the trees' bounty. Bear, deer, turkeys, and many of the forest dwellers relied on the nuts to fatten up before winter. Farmers would let their hogs and cattle loose in the woods to eat the downed nuts.  American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia Chestnut trees could grow upwards of one hundred feet and often the lower trunk would be devoid of branches, making it an ideal tree to harvest for timber. The wood was rot-resistant which made it an ideal material for use around the homestead. It was literally used from cradle to grave. People used the wood for for constructing homes, fences, furniture (including cradles) and coffins. The Chestnut tree was instrumental in the industrialization of the country. The wood was used to make rail ties for the burgeoning railroad sector after the Civil War and when the telegraph took off, the wood was milled for the poles. The Chestnut offered another valuable commodity: tannins. An industrious land owner could strip the bark off a tree and ship to a tannery where it would be boiled down and used to soften hides. The tree was so prolific and had so many uses that the loss to blight was a turning point for industries and people that relied on it for their livelihoods. Around the turn of the twentieth century scientists began to notice a strange fungus blight infecting Chestnut trees found in a park in New York City. Unfortunately, the fungus was imported to the US via other plant species and there was and is no known cure. It spread rapidly, eventually reaching the Appalachian forests by the mid-late 1920s where it wiped out huge swaths of trees. When the US government started the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933 as part of the New Deal program to counter the impacts of the Great Depression, the men recruited to work in the nation's park systems had to deal with the blight. At the time they tried various mechanisms to control the fungus, including harvesting young trees to bring to nurseries in the hopes of re-foresting the region. However, this proved fruitless because oaks and ash harbor the fungus and once Chestnuts reach a certain age, the fungus inevitably attacks. To treat trees that had the blight, the CCC used a procedure called mud-packing, covering the cankers with moist soil and wrapping the area with black tarp. This also proved unsuccessful. Trees that were beyond help were often cut and the men used the wood to make bridges, stairs, and facilities for the parks. Indeed, many structures found in US parks may be remnants of old Chestnut trees. Today there are efforts to genetically modify the native chestnut species with an Asian counter-part that is disease resistant. There are numerous research farms dedicated to re-introducing these modified Chestnut trees into the forests where they once thrived. In a matter of generations we may see a modified version of the majestic Chestnut grace our Northeastern forests once again. 3/23/2022 0 Comments The Tree Army VideoI put this video together a few years ago to highlight the work of the US Civilian Conservation Corps. During the Great Depression they planted over three billion trees in our state and national forests. As it is approaching Arbor Day and the book launch date of my novel The Truth of Who You Are set during this time and about these men (April 28, 2022) I am sharing this video. Click Below and Enjoy! 1/25/2022 1 Comment The Book That Won't Quit Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash About five years ago I was on a trip in the Orcas Islands when I learned about the men in the Civilian Conservation Corps who worked for a measly $5.00/week during the Great Depression, building infrastructure and planting over 1 billion trees in our nation's parks. Of course I'd heard of these men but never knew much about their work or their history. But after reading about the Corps, the multitude of men who hearkened from diverse geographic backgrounds, many of them first and second generation immigrants, I felt compelled to tell their story. I hadn't realized it at the time, but this book project titled The Truth of Who You Are, would become an emotional journey for me that had me doubting myself time and time again. Was it worth it? I kept asking. Let me list the tribulations to see this novel through to a publishing deal. 1) Research - since the novel is historical, I had to do research, which meant traveling to some of the sites where these men worked. Being self-funded, I launched an online crowdfunding campaign. I made a video, which took hours, and I almost made my goals. But the campaign failed and I wrote about it here. So I scaled back my travel plans to something doable - research in the Smoky Mountains, near where my parents lived in South Carolina. There was a lot of history to work with and hey, it's a tax write off, right? 2) Contests - I am a sucker for them. After winning one literary contest in 2017 for my novel The Night is Done, I figured I might be in a roll, so why not enter my work in progress to some contests , see how it goes? I entered The Truth of Who You Are in five writing contests. It gained semi-finalist status in one, and lost in two others. One is still pending. But the most heartbreaking loss was a national, prestigious contest that required I not pitch the book to anyone, no agents or publishers, until they told me it was out of the running. Five months later and two weeks before they were going to announce the winner, I still hadn't heard anything. My novel was still in the running. I couldn't believe it. The prize was $25,000 and a publishing contract. Could it be that The Truth of Who You Are had won? Everyday that I opened my email and there was no rejection I got my hopes up. My anxiety level was through the roof. I told only a few select friends and family about my anticipation. And then....rejection. 3) Publishers and Agents- I've attended numerous conferences over the past few years, pitching this novel to agents and editors at publishing houses. One editor wrote back to me with constructive feedback as well as encouraging words. "The Conservation Corps sections are terrific, I think. They really conjure time and place and show the impact of the programs on the people who participated in them and on the communities they served. And the burgeoning romance is nicely done as well." Yay! I revised and resubmitted. It was rejected. That was one of many to come from other agents and publishers, after they requested to read the whole manuscript. 4) Revise, revise, revise - the next step in the process is always to self-reflect, reexamine the manuscript and revise. At some point though one has to decide. What is the issue here? Is this novel not marketable? What do people want? Many revisions later, I adjusted the concept, and started all over again with the pitching. 5) Publishing Contract - I sent the novel to a small publisher who offed me a contract. Yay! Then I read the contract. That and a few other things led me to believe I'd be no better off than if I published it myself, so I declined. I can't even begin to tell you what a gut wrenching decision that was. 6) Giving up - I firmly believe in this novel. I know what it feels like to not believe something is worth pursuing. I have a novel I wrote about smuggling along the US/Canadian border sitting on my laptop which will never see print. But this novel, The Truth of Who You Are, is different. I've had positive feedback from several readers, people who I've only met in online writing circles. And my critique partner, who is brutally honest, told me it is my best writing so far. Recently a publisher asked me for the full manuscript and I’m waiting for their response. Their contract is posted on their website and seems more favorable. So we'll see. Like I said, this book won't quit. But I imagine, neither did these guys from the Conservation Corps. Post script: I wrote this blog in November 2019 and have since signed a contract with Black Rose Writing to publish. The novel launches April 28, 2022. You can pre-order (discounted) ebooks at the following links. 4/8/2020 Enough Already! Main entrance NY Public Library. Main entrance NY Public Library. In a interview on the History Author Show podcast about the Durant Family Saga, the interviewer asked me a question that had me stumped: If you could fill any gap about this fascinating family after three novels, what would you choose? Of course, there’s more I could have uncovered about the Durants to turn my trilogy into a series. I've received emails from people who were reading my books and my research journey blog. They offered me tidbits of information, leads to follow, contact information of descendants with interesting histories of their own. But for me, enough was enough. I’d spent five years of my life researching this Gilded Age family. I had traveled to several libraries and museums on the east coast of the U.S., and visited the Isle of Wight in England. At some point authors of historical fiction rely on conjecture. It is the lens we use to offer our interpretation of events given the information we have on hand. Indeed, at the end of the trilogy, in the novel, The Night is Done, the narrator, a historian, remarks: I’m sure that in the future, someone will come along and find gaps in my research. It’s the historian’s curse. Our job is to sift through the tall tales and determine what’s worth including and what’s best left as fodder for others to chew on. The truth is found in the abyss of the unknown. If my readers believe it’s me, the author saying these words, they aren’t far off. I put myself in the head of the narrator, a historian, tracking down and interviewing an elderly member of the Durant family, and by the time I was done writing the last book in the trilogy, it was how I felt. We read historical fiction to discover history in an interesting and entertaining fashion. Authors of this genre are all too aware that some research could take up a lifetime and if we wait for all the facts to be known, the stories would never get written. This is especially true as libraries, newspapers and museums digitize their collections making them more accessible to the public, uncovering new details and facts about historical events along the way. There are always new stories to tell, and I have moved on to tell them. My latest work in progress is about the men of the US Civilian Conservation Corps, who planted over a billion tree seedlings in the US during the Great Depression. The story revolves around the families who once lived in Cades Cove, a cultural heritage site at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. After doing research about these families, I felt compelled to tell their stories. And I hope to have this novel published soon.You can read the first couple of chapters here. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed