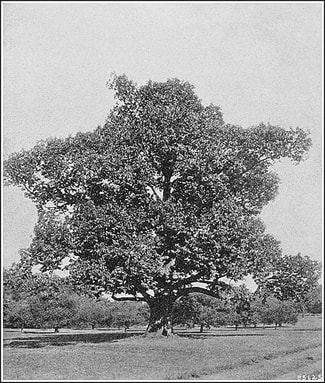

American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia The story of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) is tragic but hopeful. At one time the Chestnut tree was prolific in the northeastern US. At the turn of the 19th century, the Chestnut covered over twenty-five percent of the Appalachian mountain range which runs from Maine to Georgia. However, an imported fungus first discovered in 1904 destroyed much of the Chestnut forests. The Chestnut tree was an integral part of the landscape and had many uses. Indigenous people had multiple names for the tree's nuts, which they ground them down for flour. Families that moved into the Appalachian region foraged the nuts to eat and sell. But people weren't the only consumers of the trees' bounty. Bear, deer, turkeys, and many of the forest dwellers relied on the nuts to fatten up before winter. Farmers would let their hogs and cattle loose in the woods to eat the downed nuts.  American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia Chestnut trees could grow upwards of one hundred feet and often the lower trunk would be devoid of branches, making it an ideal tree to harvest for timber. The wood was rot-resistant which made it an ideal material for use around the homestead. It was literally used from cradle to grave. People used the wood for for constructing homes, fences, furniture (including cradles) and coffins. The Chestnut tree was instrumental in the industrialization of the country. The wood was used to make rail ties for the burgeoning railroad sector after the Civil War and when the telegraph took off, the wood was milled for the poles. The Chestnut offered another valuable commodity: tannins. An industrious land owner could strip the bark off a tree and ship to a tannery where it would be boiled down and used to soften hides. The tree was so prolific and had so many uses that the loss to blight was a turning point for industries and people that relied on it for their livelihoods. Around the turn of the twentieth century scientists began to notice a strange fungus blight infecting Chestnut trees found in a park in New York City. Unfortunately, the fungus was imported to the US via other plant species and there was and is no known cure. It spread rapidly, eventually reaching the Appalachian forests by the mid-late 1920s where it wiped out huge swaths of trees. When the US government started the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933 as part of the New Deal program to counter the impacts of the Great Depression, the men recruited to work in the nation's park systems had to deal with the blight. At the time they tried various mechanisms to control the fungus, including harvesting young trees to bring to nurseries in the hopes of re-foresting the region. However, this proved fruitless because oaks and ash harbor the fungus and once Chestnuts reach a certain age, the fungus inevitably attacks. To treat trees that had the blight, the CCC used a procedure called mud-packing, covering the cankers with moist soil and wrapping the area with black tarp. This also proved unsuccessful. Trees that were beyond help were often cut and the men used the wood to make bridges, stairs, and facilities for the parks. Indeed, many structures found in US parks may be remnants of old Chestnut trees. Today there are efforts to genetically modify the native chestnut species with an Asian counter-part that is disease resistant. There are numerous research farms dedicated to re-introducing these modified Chestnut trees into the forests where they once thrived. In a matter of generations we may see a modified version of the majestic Chestnut grace our Northeastern forests once again.

2 Comments

Jane

4/9/2022 11:04:47 am

Lots of interesting information. Thanks! We used to have a few chestnuts remaining in our town and you've inspired me to seek them out to see if they're still there. It's an amazing ecological story.

Reply

Sheila Myers

4/9/2022 11:33:18 am

I'm glad you enjoyed the story.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed