|

12/1/2022 2 Comments Gendered Ethnographies Anyone researching the Appalachian culture at the turn of the 20th century is likely to find the ethnographies of Emma Bell Miles and Horace Kephart. Miles’ The Spirit of the Mountains (1905) and Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders (1913 and 1922) document the daily lives of the people living in the mountains of the southeast United States in the early 1900s. Their lyrical prose on the familial culture, unique dialect, art and music—influenced by isolation—are entertaining and insightful reads. Emma was the inspiration for Ben Taylor's mother, in my novel The Truth of Who You Are, set in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. I found her personal story both tragic and inspiring. And the contrast of Emma Bell Miles' fate compared to Horace Kephart, (considered legendary in the region for advancing the National Park) smacks of irony. So I delved into to their personal lives further. And this is what I found. An examination of these two authors reveals parallels in their writing style and the influence their education had on their perception of the culture. Emma went to college for two years at the St. Louis School of Art. Horace attended college in the mid-west and then went on to graduate school at Cornell University in 1881 to study history and political science. Both authors had educations that were for the most part beyond that of the people they were studying. Rather than condescending, the authors had a penchant for describing their neighbors with grudging respect and awe for their resiliency. Moreover, both authors were amateur naturalists. Kephart wrote numerous articles for magazines such as Field and Stream on camping and the flora and fauna of the region, while Miles wrote and illustrated a book titled Our Southern Birds, in 1919. Both weave vivid narratives of the natural beauty of the region throughout the Spirit of the Mountains and Our Southern Highlanders.

2 Comments

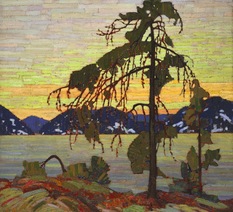

11/14/2018 Tracking Stories in the Algonquin Wilderness Jack Pine by Tom Thomson Source: Wikimedia Jack Pine by Tom Thomson Source: Wikimedia Writing placed-based literature is a great experience because there are always stories embedded in the culture of an area that a writer can use as a springboard. When I wrote Ephemeral Summer I placed my college-age protagonist, Emalee, in settings that were familiar to me. She attends college in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York because I know the area well. However, like most college-age students she moves around, and in the last chapter, she visits the Canadian wilderness to assist a fellow graduate student track moose in Algonquin Provincial Park in Canada. Although I had stayed in Algonquin twice myself during graduate school (tracking moose), my research on Algonquin went beyond the ecological setting and into the realm of art. While conducting my research I was surfing the Internet for information about the Northern Lights to include in the novel, and stumbled upon the artwork of Tom Thomson, (1877-1917) an artist from the early 1900s who painted landscapes in Algonquin. Thomson first visited Algonquin in 1912 and fell in love with the place. He stayed, found jobs as a ranger, firefighter and any other occupation that the woods would allow, and painted in his spare time. His paintings are considered the forerunner of a movement of painters called The Group of Seven: a group of Canadian landscape painters who spent considerable time painting in Algonquin from the 1920s-1930s. As I delved into his story I found parallels to my plot. There is an accidental death by drowning in my story Ephemeral Summer, and Thomson likewise drowned under mysterious circumstances. In 1917, at age 40, he went out canoeing and was found dead a week later. Foul play was suspected but never confirmed. Like many artists, Thomson did not make a lot of money on his works. Although he did have a patron, and some of his works sold, he became more popular after his death. And that is what is most intriguing about Thomson: his drive to create art whether it sold or not. His story folded neatly into my narrative for Ephemeral Summer. Indeed, for many artists, who create for art's sake, because they feel compelled. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed