A red maple planted with students. A red maple planted with students. I've used this tag line in my biographies several times and although it's metaphorical, it's also true. In my professional capacity over the years as an outdoor educator and professor teaching ecology and environmental science, I've worked alongside volunteers and students planting trees. Together we've planted hundreds of seedlings and bare root mature trees in places such as the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, the City of Syracuse parks, and the nature trail behind the college campus where I teach. So you can imagine my chagrin when we were approached by the utility company with a request to take down the ash trees that line the front of our house. The Emerald Ash borer is wreaking havoc on ash trees in the Northeastern U.S. and our ash trees are directly under the utility wires. The emerald ash borer beetle lays eggs in the tree's bark and the larvae eat away at the phloem, the inner part of the bark that transports water and nutrients, eventually killing the tree. The borer is not native to the United States and was brought to the states accidentally in 2002 from Asia. Within the decade our trees would be dead so we agreed to let the utility take them down. We then had to decide whether to take down the magnificent ash tree in our side yard.  This tree was planted long before we arrived, I'm guessing its age at fifty plus years. Its largess allowed it to throw shade on the back deck. Great! Except when you live in Upstate, NY and summers are so short. Half the tree hung over the driveway and in the fall it shed dead limbs and leaves like crazy. We spent hours cleaning up the mess it left on the pavement after a wind storm. So although I loved the tree we decided to take that one down as well. As upsetting as it was to see the hole in the sky when the tree was felled, this summer we've witnessed spectacular sherbet colored sunsets now that the limbs aren't obstructing the view.  It wasn't long however before the gaping hole in the landscape gnawed at me and we went in search of a new tree. I chose a redbud because I love the way their lavender flowers bloom so delicately in the spring. And they don't get that big - maybe twenty-five feet in height. Even as we were debating whether to take the ash tree down I knew I'd end up planting another in its place; I've spent the past few decades educating and advocating for the natural world. And I'm always rewarded by the look of wonder and accomplishment that passes over people's faces after grubbing around in the dirt, digging holes, putting in a tree, heeling the rich earth back into place. I remember one day in particular while planting thirty trees with my students in the nature trail behind campus. I was crouched over a dug-out hole, wide enough to handle the bare roots of a red maple. I was working with a student, using a shovel to back-fill the hole with dirt, when the student told me, "I've never planted a tree." He sat back on his haunches sweating and wiping at his brow with the back of his hand. "Well," I told him, "this is something you won't forget." I eyeballed the sky. "And if you do, come back one day to see how much it has grown."

2 Comments

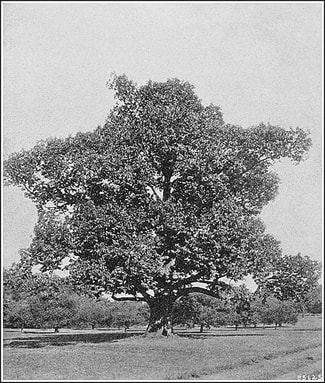

Apple Trees by Levi Wells Prentice circa 1890 Source: Wikimedia Apple Trees by Levi Wells Prentice circa 1890 Source: Wikimedia Drive through any rural area of the U.S. and you will inevitably find apple orchards; some may be new, others may be reminders of a family homestead long abandoned. But the trees remain. It's believed that the Pilgrims brought apple seeds with them to the American colonies when they arrived in the early 1600s and grafted the European variety with the native American species of crab apple. Over the years farmers created many new varieties of apples. But not for eating. Apple trees and orchards had other economic uses. One of the first things a settler would do is plant an apple orchard as a way to stake claim to a parcel of land. When investors formed the Ohio Company to lure colonists from the eastern states further West, they insisted the settlers plant at least fifty apple trees to establish their claim. Apples provided an important part of the American diet: cider. Most colonists used their apples to make cider, which was safer to drink than water. Indeed, one of out of every ten farms in New England operated a cider mill. Estimates are that an average New England family consumed about 35 gallons per person per year. (The author, Tracy Chevalier, wrote a historical novel centered around a family in Ohio that grows cider apples titled At the Edge of the Orchard. Although dark, it includes a fascinating botanical history.) By the mid 1700s, orchards were an integral part of the American landscape. And although it may be assumed that the European settlers were the only ones to plant orchards, there was ample evidence that Native Americans also incorporated orchards into their lifestyle. In 1779, a scout for the Revolutionary Army drew a map of the Cayuga and Seneca native American settlements in the Finger Lakes region of New York. As the map shows, there were numerous orchards dotting the landscape. General Sullivan, ordered his soldiers to go into the villages and wipe out the crops in retribution for an Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) incursion against the army. One soldier wrote in his diary about an attack on a village in what is now Geneva NY: we found about 80 houses something large some of them built with hew and timber and part with round timber and part with bark. Large quantities of corn and beans with all sorts of sauce, at this place a fine Young Orchard, which was soon all girdled.  American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia The story of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) is tragic but hopeful. At one time the Chestnut tree was prolific in the northeastern US. At the turn of the 19th century, the Chestnut covered over twenty-five percent of the Appalachian mountain range which runs from Maine to Georgia. However, an imported fungus first discovered in 1904 destroyed much of the Chestnut forests. The Chestnut tree was an integral part of the landscape and had many uses. Indigenous people had multiple names for the tree's nuts, which they ground them down for flour. Families that moved into the Appalachian region foraged the nuts to eat and sell. But people weren't the only consumers of the trees' bounty. Bear, deer, turkeys, and many of the forest dwellers relied on the nuts to fatten up before winter. Farmers would let their hogs and cattle loose in the woods to eat the downed nuts.  American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia Chestnut trees could grow upwards of one hundred feet and often the lower trunk would be devoid of branches, making it an ideal tree to harvest for timber. The wood was rot-resistant which made it an ideal material for use around the homestead. It was literally used from cradle to grave. People used the wood for for constructing homes, fences, furniture (including cradles) and coffins. The Chestnut tree was instrumental in the industrialization of the country. The wood was used to make rail ties for the burgeoning railroad sector after the Civil War and when the telegraph took off, the wood was milled for the poles. The Chestnut offered another valuable commodity: tannins. An industrious land owner could strip the bark off a tree and ship to a tannery where it would be boiled down and used to soften hides. The tree was so prolific and had so many uses that the loss to blight was a turning point for industries and people that relied on it for their livelihoods. Around the turn of the twentieth century scientists began to notice a strange fungus blight infecting Chestnut trees found in a park in New York City. Unfortunately, the fungus was imported to the US via other plant species and there was and is no known cure. It spread rapidly, eventually reaching the Appalachian forests by the mid-late 1920s where it wiped out huge swaths of trees. When the US government started the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933 as part of the New Deal program to counter the impacts of the Great Depression, the men recruited to work in the nation's park systems had to deal with the blight. At the time they tried various mechanisms to control the fungus, including harvesting young trees to bring to nurseries in the hopes of re-foresting the region. However, this proved fruitless because oaks and ash harbor the fungus and once Chestnuts reach a certain age, the fungus inevitably attacks. To treat trees that had the blight, the CCC used a procedure called mud-packing, covering the cankers with moist soil and wrapping the area with black tarp. This also proved unsuccessful. Trees that were beyond help were often cut and the men used the wood to make bridges, stairs, and facilities for the parks. Indeed, many structures found in US parks may be remnants of old Chestnut trees. Today there are efforts to genetically modify the native chestnut species with an Asian counter-part that is disease resistant. There are numerous research farms dedicated to re-introducing these modified Chestnut trees into the forests where they once thrived. In a matter of generations we may see a modified version of the majestic Chestnut grace our Northeastern forests once again. And that's ok."  It has taken me a whole year - and I'm not quite finished yet - to read the Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Overstory. And it has been a struggle to get as far as I have in the book. The first part of the book introduces the reader to eight characters. From then on, each chapter, even within chapters if you can call them chapters, reveal a new point of view from characters that you are supposed to remember being introduced to a number of pages prior. It's all very confusing and I would have given up if not for the fact that the writing is so beautiful. It's about trees, but also about human connection to trees and the will of some to fight for trees to be treated as a legal entity - with rights. The most interesting part to me has been the description of a couple who climb a mammoth Redwood in Oregon to try and save it from loggers. The vivid scenes of them swaying in the wind and watching the stars at night made me wonder if the author, Richard Powers, had actually stayed in a tree house to write about the experience. I started the novel before Covid lockdowns, having heard some recommendations from friends. I've spent most of my career educating about and advocating for the natural world so I thought, right up my alley. Once Covid hit and I got into the middle part of the story where the chapters intertwine various characters, my head started to spin and I lost interest. I relegated the book to the shelf in the basement where I keep books to donate to the library for their annual sale. Wouldn't you know it, the library closed and there was no sale. So when our book club met outside around a fire pit one cool evening in the late summer I was reminded about the book by a friend who had finished and loved it. "Maybe I'll give it another try," I thought. I dug it out of the pile of books that had been accumulating all year and started reading again. I didn't bother going back to figure out who was who because I decided the best way to get to the end was not to worry if I couldn't keep track. Life has been like that with Covid. I try not to worry too much about things I can't control (like someone else's story structure) so that I can enjoy the day to day living that is required to get by in these trying times. If I can keep my health, take a walk, talk to my family, and pet my cats, I'd say my life is pretty full. I have a lot to be grateful for. So if it takes me another year to finish this book (because I now have two more books I'm reading sitting by bed stand and on my Kindle), then who cares? I'm just relishing the writing. I'm just enjoying the pleasure of reading while I am able. 9/2/2020 Wearing Our Feathered Friends While reading Edith Wharton’s Age of Innocence, set in the 1870s in New York City, I remember being taken aback by a reference to a woman carrying a fan made of Eagle feathers to the opera. Oh dear, I thought. Our national bird? A protected species? Why, just recently they stopped construction of a dock near my hometown because a pair of Eagles were nesting in the trees nearby. Then during the course of my research for my second novel in the Durant family trilogy, I came across a reference to William West Durant taking off with an Adirondack guide to shoot three Loons that had the bad luck to be stuck in a cove as it had iced-over one night in early spring (1890). Loons are heavy and can’t take off without a flyway and so, as the memoir I found at the Adirondack Museum goes, the Loons managed to keep a small opening in the ice during the night but needed the cove to melt so that they had enough space to take off. Unfortunately, they never got that chance (you’ll have to read story two to find out what happens to them). I was aghast. My modern sensibilities get in the way of my research at times. While describing ladies’ fashions during the Victorian era I had to contend with the fact that women loved wearing the artifacts of dead birds on their hats or to adorn their outfits. After all, it wasn’t until Boston socialite Harriet Hemenway and her cousin Minna started a a boycott against the practice of hunting exotic birds down to adorn lady’s hats in 1896 that the abomination of the practice came to light. Indeed, these two lady mavericks are credited with starting the Audubon Society to save birds from extinction. They first heard about the plight of birds after an amateur ornithologist, Frank Chapman, wrote about his experience watching bird hunters go after an egret rookery, plucking the feathers and leaving the young to die in the trees. Chapman is also credited with surveying for birds on the streets of New York City. In one day in 1886 Chapman counted 542 hats adorned with 174 whole birds or their parts. He claimed to have counted over forty different species of birds on ladies’ hats: pheasants, peacocks, egrets, scarlet tanagers, robins, and blue jays, just to name a few. It wasn’t until the turn of the century that it started to become unfashionable to be wearing a dead bird on one’s head, much less a bird that was considered endangered. This points to the fact that at the time, people believed our resources to be limitless, or never knew the difference and didn’t care. 5/10/2020 The Fox Family in the Local Cemetery There is a family of red fox in a cemetery nearby and they have become a welcome diversion from all of the doom and gloom of the Covid-19 pandemic. I've been finding myself wandering the cemetery in the early morning and evenings, hoping to observe the pups playing. When the mother comes around, I take off so as not to distract them from their feeding routine. Watching them from a distance allows me to keep my mind off of other pressing concerns (the health and safety of my family) and made me realize that as we humans struggle with the impacts of this terrible pandemic, mother nature just keeps forging on. Because the red fox appears in two of my novels, I researched their ecology. Fox mate in late winter and produce 2-10 young by March-April. The mother builds two dens (one is a back-up). They may dig their own or take over previous holes dug by gophers. It is not uncommon for the mother to divide the litter between two dens. Unlike some other mammals that leave the care of the young to the mother, fox mates stay together to bring up the pups. The male will bring food for the pups to play with and eat until they can hunt on their own (12 weeks). They are omnivores, meaning they eat both meat and plants. I've seen bird feathers and carcasses near the den and one day I spotted one of the parents coming over the hill with what looked like a squirrel in its mouth. They are mostly active in the early evening or night but while taking care of the young, the parents may be seen hunting near the den. Sometimes at night I can hear the screeching and yipping of fox that live in the fields near our house. It's slightly eerie and almost sounds like they are in pain. This form of communication is mostly between mates. After 12 weeks, the pups disperse - males going first, to stake out new territory. The coyote and man are the fox's natural predators. It is still legal to hunt fox in the U.S. but not as common as it used to be. While I was researching one of my novels I found a reference to residents of the Smoky Mountains during the Great Depression, hunting fox and other fur bearing mammals to send the pelts to Sears and Roebuck for five dollars a pelt. And of course many of us know about fox hunting with hounds which has been banned in most places. In the U.S. it is now considered a 'chase' and they don't kill the fox. Nowadays, the lethal risk to fox is the coyote, which is increasing in number in the Northeaster U.S. , and disease. Since the stay-at-home and social distancing began I've been walking three to four miles a day to keep my mind off things. Checking in on the fox family has become a ritual and has saved me from wallowing in despair. It has also served as a reminder that the Mother nature keeps moving on no matter what we humans do. We will survive all of this. If anything, slowing down, walking outdoors because the gyms are closed, has been a godsend for a lot of us because we're reconnecting with the natural world. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed