Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Me sitting along fireplace at one of the cabins. Cades Cove Before it became a national park that draws more than 12 million people a year, The Smoky Mountains National Park was home to the Cherokee, and after that, settlers from Europe. They settled in the ‘coves’ or flat valley areas in the mountains which allowed them to raise crops and livestock. They had churches, schools, unique cantilevered barns, henhouses, and cabins. Thankfully, a historian had the foresight to encourage the government to preserve homesteads in the park as cultural heritage sites. And that is where the research journey for my novel, The Truth of Who You Are began. What drew me first to the region (besides the majestic mountains) were the stories of the people who once inhabited Cades Cove. The community structures are still intact, preserved by the park for visitors to witness what it may have been like growing up in the shadows of the mountains. Regional museums have books about the people who once lived in the area, how they conducted business, and lived before the government bought them out to make the national park during the Great Depression. This eleven-mile circuit holds what remains of an entire community that once lived there: homes, corn cribs, barns, smoke, and spring houses.

0 Comments

4/26/2024 Following The Past to Where It Leads MeFollow the people from the past, the places they lived, worked, politics, public sentiment, changing landscape, and a narrative emerges that's worth telling in fiction. While climbing the viewing tower on Mount Constitution in Washington State, I had the opportunity to read the testimony of the men who built it and was hooked on their story. A particular sign caught my eye. It was a certificate of appreciation to one of the men who helped build the tower in 1936, thanking him for being part of an "Army of Youth and Peace" and "Awakening the People to Conservation and Recreation." The men who built the Mt. Constitution viewing tower and much of the infrastructure at the park, served in the U.S. Tree Army, a.k.a the Civilian Conservation Corps. (CCC). They led ordinary lives during an extraordinary time in U.S. history: the Great Depression. These men, recruited from cities, rural towns and Indian Reservations from 1933-1939, served the U.S. citizenry and had an enormous impact on cultural attitudes toward conserving the natural resources, especially National and State forests. Their nickname: The Tree Army, is apt; estimates are they collectively planted over three billion trees across the country. They fought numerous forest fires ravaging lands that were cut over and neglected by private lumber companies, and they prevented the decimation of the Great Plains agricultural lands through their soil conservation works. And they were paid $30.00/month and given three meals a day to do so. The rest, $25.00, was sent home to support their families. Five dollars a month may sound like a paltry sum, but during the Depression, it was a king's salary to these men. "Five dollars a month made me rich! I never had $5.00 before in my life." They were between the ages of 17-30. Some were World War I veterans. All were on public assistance. The U.S. Surgeon General estimated that 75% of the 100,000 men they examined in one year, were malnourished, prone to disease and exhausted from stress and the search for work. As one CCC alum wrote, the men had the mark of shattered ambitions and blasted hopes written on their faces. Although the CCC was touted as a jobs recovery program, and a way to keep men, particularly immigrants from roaming city streets looking for work, President Franklin Roosevelt also had a keen interest in preserving national park land. During his administration the Federal government acquired vast amounts of land and put it in the public domain. Soon, CCC camps were popping up in rural enclaves throughout the U.S. where there were plenty of public work projects to be done. Besides planting trees these men built roads, cabins, lodges, rest areas, bridges, and scenic byways in the parks. And their presence played a big role in improving the economies of the surrounding towns. Local supplies, carpenters, and tradesmen were employed to help build and service the CCC camps and the local businesses: theaters, barbershops, food stores, all catered to them. The Tree Army had an enormous impact on the recreation and tourist industry. Back in 1930 the Great Smoky Mountains National Park had about three thousand visitors a year. By the end of that decade, and due to their work, over 130 thousand visitors came to visit. Today the park welcomes over ten million visitors/year. While reading the testimony of the men in various written accounts, one can imagine how hard it was, especially for the city dwellers, to be sent into the woods, so far from home, even if they were surrounded by awe-inspiring beauty. Most didn't have a high school education and had never traveled outside their own city neighborhoods. One man stated he and the other recruits were pensive when they landed at a Washington port to be shipped out to the San Juan Islands. They didn't believe it when they were told by their camp leader the Islands were part of the United States, instead thinking they were being deported. When Orson Welles broadcast the War of the Worlds on radio in 1938, some of the men panicked, believing their homes in the Northeast were being destroyed by an invasion of martians. As one alum recounted, the boys from the east coast cities were screamin' and hollerin' around the camp. After reading about the men in the CCC, I went looking for fictional accounts and didn't find many. That's when I decided it was time to tell their stories. In April 2022, The Truth of Who You Are was published by Black Rose Writing. A coming of age story about hope and resilience and set at one of the CCC camps in the Smoky Mountains NP. Sources:

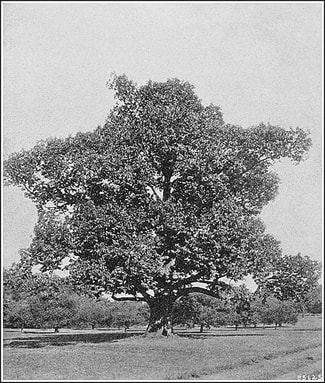

Olympic Mountain Range from Mt. Constitution, Moran State Park, Orcas Island. Photo credit Wikimedia: Lee317 Brinkley, Douglas. Rightful Heritage. HarperCollins 2016. Hill, Edwin. In The Shadow of the Mountain. Washington State University Press 1990. Jolley, Dr. Harley. The Maginficent Army of Youth and Peace. UNC Press. 2007. Maher, Neil. Nature's New Deal. Oxford University Press 2009. 3/26/2023 My Segmented Reality Photo by Monica Silva on Unsplash Photo by Monica Silva on Unsplash I'm a mother, wife, educator. I'm a writer. Although I try to remain in the present, I find my mind wandering to the depths of my imagination, attempting to tease out the next scene in my novel, a character flaw, joy, despair. I am stretched to capacity to create. Between lesson plans on critical thinking, what to make for dinner, how I'm going to kill off one the characters in my novels, my mind has limited time to stay in the moment. Even in the car, while driving to and from different campus sites I listen to podcasts, gleaning inspiration on writing, marketing, thinking. Oprahs's Super Soul Conversation reminds me what I should be doing: "Time to be more fully present.....starts right now." I'm soooo sorry Oprah - I listen to your podcast once a week, gaze at the rural landscape streaking past my window, warm earth interspersed with golden corn stubble from last year's harvest, a flock of white geese taking flight, sparkling like dust motes in the March sun. And oh, what did Amy Purdy just say about resilience? I was framing the moment for a scene in my next novel. I can't be the only one with a creative mindset trapped in the mundane day-to-day responsibilities that keep the family going, the heater operating as winter clings; I learned from a New York Times article, it's true. Many famous artists and writers maintained separate, working lives. Does it mean they produced better art? I know I feel a pressure to create whenever there is a moment: an hour on a Saturday, winter break, spring break, summer. I develop timelines around my school schedule, can I get to 50k words by May? How many weekends and breaks do I have? How much grading to do? Will one of my daughters be in town for the weekend? If I had more time, if my life weren't segmented into pieces of me, I'm not sure I'd be any better at my craft. As someone close to me once said, 'you work better under pressure, with deadlines'. I don't meander once I sit down to write, the words come to me, have been building over time, while driving, in my journals, in my dreams. My characters speak to me. And I don't let them down. 12/2/2022 Hope: a Gift from World War II U.S. Troops sorting holiday mail 1944. Source Wikimedia U.S. Troops sorting holiday mail 1944. Source Wikimedia The Truth of Who You Are has a major part set during the Battle of the Bulge in World War II. This epic military campaign began in the foreboding Ardennes Forest December 16, 1944 and was not concluded until January 1945. The Germans had amassed a large army hidden in the forests along the ridges and deep ravines of the Ardennes mountains of eastern Belgium and France. The Germans' objective was to take the city of Bastogne and the port of Antwerp. Unsuspecting American soldiers from the 110th Infantry were recuperating from the brutal battle in the Hürtgen Forest in the town of Clervaux. And when the Germans began their offensive, the Army was taken by surprise. Although the Germans would eventually be defeated, it was an epic battle. Infantrymen recount the eerie presence of German soldiers camouflaged in white outer-coats to match the snow, moving like wraiths in and out of the cover of fir trees on the battlefield. By the time it was over, 75,000 American and 80,000 German soldiers perished in the Ardennes. While looking for primary sources I landed on a book titled: I'll Be Home for Christmas. It's a compilation of soldiers' letters and essays from the U.S. Library of Congress focused on the period of time soldiers' memories of home were most precious. The chapters include passages where they describe the movement of the infantry through the dark fir forests of the Ardennes, trudging through snow up to their thighs, hiding in fox holes, reminiscing about the holiday. More than once, the gravity of the moment was interspersed with small wonders and gestures of humanity. As one of the survivors, who was holed up in a cellar on Christmas Eve recalled: "At the stroke of midnight, without an order or request, dark figures emerged from the cellars. In the frosty gloom voices were raised in the old familiar Christmas carols. The infantry....could hear voices two hundred yards away in the dark, in German,...singing Silent Night." They decorated random trees with tin ration cans. They made the best of a situation while pining to be home. Some of the men who were separated from their units ended up in cabins of the locals who gave them refuge and food on Christmas Eve. A medic was given a wooden carving from a piece of packing crate with the word Weihnachten 1944 (Christmas in German) from one of the German prisoners of war he treated. A Belgium schoolteacher, returning to his classroom after the battle found this written on the blackboard by a German officer: May the world never live through such a Christmas night. Nothing is more horrible than meetings one's fate, far from mother, wife, and children..... Life was bequeathed us in order that we might love and be considerate to one another. From the ruins, out of blood and death shall come forth a brotherly world. One of the more poignant stories comes from bomber pilot Philip Ardery who knew all too well that fate might never give him another Christmas. He was reminded of this everyday while flying over Europe during the month of December of 1943. Growing up, he never opened any presents before Christmas Day. By late November family members of the pilots were sending packages to the headquarters where he was stationed. Many sat unopened, a 'Return to Sender' stamped on them when a soldier failed to return from a flight. Yet when Ardery was sent out on a mission in the inky dark of a bracing cold dawn, he had to decide: should I open one of my gifts just in case I don't make it back? His family and friends made sure he had plenty to open. Each night he considered them from the perch of his bunk; the packages, sitting there waiting for him to rip open and discover what was inside. Making it even more difficult was the fact that the weather was horrendous. Heavy fog and cold, damp air was hindering the pilots' efforts. Because they had not received their pathfinder equipment on time, they were flying without the instruments needed to guide the bombing. As a result, there were many mid-air collisions. In addition, lack of adequate gear meant men returned from their mission with frostbitten hands and many had to be hospitalized. As the casualties mounted, each day, Ardery asked himself: should I open my presents just in case I don't make it back alive? Indecision plagued him through the month of December. He didn't. He said the gifts were magical because of who sent them, those he held dearest. Maybe it was the taboo of opening anything before Christmas. Maybe it was hope. Hope that he would make it through his mission to eventually return home to those people he held dear. Hope may have been the greatest gift he received that year, that along with his life. He eventually opened his gifts on Christmas Day. One of the lucky ones to return home to family. 12/1/2022 2 Comments Gendered Ethnographies Anyone researching the Appalachian culture at the turn of the 20th century is likely to find the ethnographies of Emma Bell Miles and Horace Kephart. Miles’ The Spirit of the Mountains (1905) and Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders (1913 and 1922) document the daily lives of the people living in the mountains of the southeast United States in the early 1900s. Their lyrical prose on the familial culture, unique dialect, art and music—influenced by isolation—are entertaining and insightful reads. Emma was the inspiration for Ben Taylor's mother, in my novel The Truth of Who You Are, set in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. I found her personal story both tragic and inspiring. And the contrast of Emma Bell Miles' fate compared to Horace Kephart, (considered legendary in the region for advancing the National Park) smacks of irony. So I delved into to their personal lives further. And this is what I found. An examination of these two authors reveals parallels in their writing style and the influence their education had on their perception of the culture. Emma went to college for two years at the St. Louis School of Art. Horace attended college in the mid-west and then went on to graduate school at Cornell University in 1881 to study history and political science. Both authors had educations that were for the most part beyond that of the people they were studying. Rather than condescending, the authors had a penchant for describing their neighbors with grudging respect and awe for their resiliency. Moreover, both authors were amateur naturalists. Kephart wrote numerous articles for magazines such as Field and Stream on camping and the flora and fauna of the region, while Miles wrote and illustrated a book titled Our Southern Birds, in 1919. Both weave vivid narratives of the natural beauty of the region throughout the Spirit of the Mountains and Our Southern Highlanders. 6/23/2022 1 Comment Finding Purpose I'm revisiting blog posts from the past and this one struck me because I just finished launching my fifth novel and this same feeling of loss can be overwhelming. If I let it be. This morning I was listening to Ann Lamott's book Small Victories: Spotting Improbably Moments of Grace, and her first lines just jolted me: "The worst possible thing you can do when you’re down in the dumps, tweaking, vaporous with victimized self-righteousness, or bored, is to take a walk with dying friends. They will ruin everything for you." I have not, I must admit, recently walked with a friend who is close to death, but I could relate to what Lamott was saying. Lately I have been wallowing a bit too much in self-pity, for no reason whatsoever except perhaps because I have completed my novel and although I'm working on the next, I definitely feel a sense of loss. And, I must admit, although I never started on this journey for the accolades, (and most obviously not for the money) there are moments when I wish that everyone I meet at the coffee shop, or passing by on the street would just say to me: "Hey, I heard you wrote another book. Congratulations," even if they have never read any of my work. I was at a picnic a few weeks ago and something like this happened and I was amazed at how much it lifted my spirits. A man came up to me, someone I know through my children, and he told me he had read one of my novels: Ephemeral Summer, and he loved it. I was a bit shocked. It is a coming of age story and the target audience would be his college-age daughters. "Everyone in the family has read it," he told me, "We loved it." I'd like to believe I'm not vain. But maybe I am. Or maybe these feelings I'm experiencing are meant to teach me something. How often I have neglected to tell someone that what they did or are doing is worthy: my friend who spent a year volunteering on a political campaign for a candidate I didn't plan to vote for; or another, who spent 6 months learning to become a yoga instructor. And then there is my friend who opened her own shop; and another friend who drove almost every weekend this past spring, over 11 hours in the car, one way, to watch her daughter play college ball. Finally, there are more than a few, who have had to sit by the side of their loved ones while they undergo treatments, trying to keep the faith. What dedication. My own family members have started new jobs, struck out on their own, or started up support groups. Congratulating them, or even making some commentary on their hard work is something I think, I should remember to do, if for no other reason than because they are trying. They are living life the way it was meant to be lived: with purpose.  A red maple planted with students. A red maple planted with students. I've used this tag line in my biographies several times and although it's metaphorical, it's also true. In my professional capacity over the years as an outdoor educator and professor teaching ecology and environmental science, I've worked alongside volunteers and students planting trees. Together we've planted hundreds of seedlings and bare root mature trees in places such as the Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge, the City of Syracuse parks, and the nature trail behind the college campus where I teach. So you can imagine my chagrin when we were approached by the utility company with a request to take down the ash trees that line the front of our house. The Emerald Ash borer is wreaking havoc on ash trees in the Northeastern U.S. and our ash trees are directly under the utility wires. The emerald ash borer beetle lays eggs in the tree's bark and the larvae eat away at the phloem, the inner part of the bark that transports water and nutrients, eventually killing the tree. The borer is not native to the United States and was brought to the states accidentally in 2002 from Asia. Within the decade our trees would be dead so we agreed to let the utility take them down. We then had to decide whether to take down the magnificent ash tree in our side yard.  This tree was planted long before we arrived, I'm guessing its age at fifty plus years. Its largess allowed it to throw shade on the back deck. Great! Except when you live in Upstate, NY and summers are so short. Half the tree hung over the driveway and in the fall it shed dead limbs and leaves like crazy. We spent hours cleaning up the mess it left on the pavement after a wind storm. So although I loved the tree we decided to take that one down as well. As upsetting as it was to see the hole in the sky when the tree was felled, this summer we've witnessed spectacular sherbet colored sunsets now that the limbs aren't obstructing the view.  It wasn't long however before the gaping hole in the landscape gnawed at me and we went in search of a new tree. I chose a redbud because I love the way their lavender flowers bloom so delicately in the spring. And they don't get that big - maybe twenty-five feet in height. Even as we were debating whether to take the ash tree down I knew I'd end up planting another in its place; I've spent the past few decades educating and advocating for the natural world. And I'm always rewarded by the look of wonder and accomplishment that passes over people's faces after grubbing around in the dirt, digging holes, putting in a tree, heeling the rich earth back into place. I remember one day in particular while planting thirty trees with my students in the nature trail behind campus. I was crouched over a dug-out hole, wide enough to handle the bare roots of a red maple. I was working with a student, using a shovel to back-fill the hole with dirt, when the student told me, "I've never planted a tree." He sat back on his haunches sweating and wiping at his brow with the back of his hand. "Well," I told him, "this is something you won't forget." I eyeballed the sky. "And if you do, come back one day to see how much it has grown."  Apple Trees by Levi Wells Prentice circa 1890 Source: Wikimedia Apple Trees by Levi Wells Prentice circa 1890 Source: Wikimedia Drive through any rural area of the U.S. and you will inevitably find apple orchards; some may be new, others may be reminders of a family homestead long abandoned. But the trees remain. It's believed that the Pilgrims brought apple seeds with them to the American colonies when they arrived in the early 1600s and grafted the European variety with the native American species of crab apple. Over the years farmers created many new varieties of apples. But not for eating. Apple trees and orchards had other economic uses. One of the first things a settler would do is plant an apple orchard as a way to stake claim to a parcel of land. When investors formed the Ohio Company to lure colonists from the eastern states further West, they insisted the settlers plant at least fifty apple trees to establish their claim. Apples provided an important part of the American diet: cider. Most colonists used their apples to make cider, which was safer to drink than water. Indeed, one of out of every ten farms in New England operated a cider mill. Estimates are that an average New England family consumed about 35 gallons per person per year. (The author, Tracy Chevalier, wrote a historical novel centered around a family in Ohio that grows cider apples titled At the Edge of the Orchard. Although dark, it includes a fascinating botanical history.) By the mid 1700s, orchards were an integral part of the American landscape. And although it may be assumed that the European settlers were the only ones to plant orchards, there was ample evidence that Native Americans also incorporated orchards into their lifestyle. In 1779, a scout for the Revolutionary Army drew a map of the Cayuga and Seneca native American settlements in the Finger Lakes region of New York. As the map shows, there were numerous orchards dotting the landscape. General Sullivan, ordered his soldiers to go into the villages and wipe out the crops in retribution for an Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) incursion against the army. One soldier wrote in his diary about an attack on a village in what is now Geneva NY: we found about 80 houses something large some of them built with hew and timber and part with round timber and part with bark. Large quantities of corn and beans with all sorts of sauce, at this place a fine Young Orchard, which was soon all girdled.  American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia American Chestnut Source: WikiMedia The story of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) is tragic but hopeful. At one time the Chestnut tree was prolific in the northeastern US. At the turn of the 19th century, the Chestnut covered over twenty-five percent of the Appalachian mountain range which runs from Maine to Georgia. However, an imported fungus first discovered in 1904 destroyed much of the Chestnut forests. The Chestnut tree was an integral part of the landscape and had many uses. Indigenous people had multiple names for the tree's nuts, which they ground them down for flour. Families that moved into the Appalachian region foraged the nuts to eat and sell. But people weren't the only consumers of the trees' bounty. Bear, deer, turkeys, and many of the forest dwellers relied on the nuts to fatten up before winter. Farmers would let their hogs and cattle loose in the woods to eat the downed nuts.  American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia American Chestnut Source: Library Company of Philadelphia Chestnut trees could grow upwards of one hundred feet and often the lower trunk would be devoid of branches, making it an ideal tree to harvest for timber. The wood was rot-resistant which made it an ideal material for use around the homestead. It was literally used from cradle to grave. People used the wood for for constructing homes, fences, furniture (including cradles) and coffins. The Chestnut tree was instrumental in the industrialization of the country. The wood was used to make rail ties for the burgeoning railroad sector after the Civil War and when the telegraph took off, the wood was milled for the poles. The Chestnut offered another valuable commodity: tannins. An industrious land owner could strip the bark off a tree and ship to a tannery where it would be boiled down and used to soften hides. The tree was so prolific and had so many uses that the loss to blight was a turning point for industries and people that relied on it for their livelihoods. Around the turn of the twentieth century scientists began to notice a strange fungus blight infecting Chestnut trees found in a park in New York City. Unfortunately, the fungus was imported to the US via other plant species and there was and is no known cure. It spread rapidly, eventually reaching the Appalachian forests by the mid-late 1920s where it wiped out huge swaths of trees. When the US government started the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in 1933 as part of the New Deal program to counter the impacts of the Great Depression, the men recruited to work in the nation's park systems had to deal with the blight. At the time they tried various mechanisms to control the fungus, including harvesting young trees to bring to nurseries in the hopes of re-foresting the region. However, this proved fruitless because oaks and ash harbor the fungus and once Chestnuts reach a certain age, the fungus inevitably attacks. To treat trees that had the blight, the CCC used a procedure called mud-packing, covering the cankers with moist soil and wrapping the area with black tarp. This also proved unsuccessful. Trees that were beyond help were often cut and the men used the wood to make bridges, stairs, and facilities for the parks. Indeed, many structures found in US parks may be remnants of old Chestnut trees. Today there are efforts to genetically modify the native chestnut species with an Asian counter-part that is disease resistant. There are numerous research farms dedicated to re-introducing these modified Chestnut trees into the forests where they once thrived. In a matter of generations we may see a modified version of the majestic Chestnut grace our Northeastern forests once again.  At one time, the Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) dominated the northeastern forests of the U.S. and had multiple uses for both the Native Americans and the colonists. Its durable wood and straight trunk made it a valuable commodity during colonial times in the U.S. Because of its value, the white pine was at the center of numerous skirmishes between colonists and the men in charge of enforcing English laws on harvesting white pines for private use. White pines grow rapidly and have longevity, some living as long as four hundred years. When the colonists arrived in New England in the early 1600s, they found virginal forests of pine and discovered trees towering over 200 feet in the air with bases several feet in diameter. They also noticed how the Native Americans used the trees for utilitarian as well as medicinal purposes. Algonquins steeped the needles and inner bark to make a tea to prevent scurvy earning them the nick-name 'bark-eaters'. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois - Five Nations) culture refer to the white pine as the Tree of Peace. Historical accounts of a peace treaty agreed upon between the Mohawk, Onondaga, Seneca, Cayuga, and Oneida tribes, occurred after a meeting under the canopy of this majestic tree. And in a testament to the significance of the white pine to their culture, (the five needles represent the tribes) the tree is at the center of the Haudenosaunee seal. |

AuthorSheila Myers is an award winning author and Professor at a small college in Upstate NY. She enjoys writing, swimming in lakes, and walking in nature. Not always in that order. Archives

April 2024

CategoriesAll Adirondacks Algonquin Appalachia Award Cades Cove Canada Chestnut Trees Christmas Civilian Conservation Corps Collis P. Huntington Creativity Doc Durant Durant Family Saga Emma Bell Miles Finger Lakes Great Depression Hell On Wheels Historical Fiction History Horace Kephart Imagination National Parks Nature Publishing Review Screenplay Short Story Smoky Mountains Snow Storm Stone Canoe Literary Magazine Thomas Durant Timber Wilderness World War II Writing |

|

|

All materials Copyright 2022

Any reproduction, reprint or publication without written consent of author prohibited. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed